A Case Against the Dialectic

(Cheat Sheet Part 5) The final one

(Editor Note: This post is a script from a video series and will be published as an E-Book in the near future. This is only part one. The video is provided but the text and diagrams are below.)

A Case Against the Dialectic

Introduction: Against the Dialectic

Hi. This video is a companion-piece to my series on left-wing philosophy, where I explained the dialectic before I covered the history of left-wing philosophy and how simply it can be slotted into the dialectical model. That series constitutes a larger argument for left-wing philosophy believing in the dialectic insofar as it believes in anything.

Usually, that translates into comments about how change is a constant in the world, and implications about how humans can do anything we want if we just all cooperate, since the accompanying view of humanity is, essentially, that we become God through the dialectic. Another key aspect of this belief is that our predecessors have created the inequalities, the contradictions of the world we live in today, and that we can and should abolish all forms of inequality in order to realize ourselves as God.

Ever since Hegel posited that the dialectic was fundamental to everything, I find that most dialectical philosophy amounts to discussing and rediscovering the nuances of the dialectic, much like what you could find in discussions of theology. This is not surprising, since the idea that we become God is theological.

I write this because I think that the dialectic is an intellectual catastrophe. It offers pretend-certainty based on assuming the correctness of dubious premises. A key expression of the dialectic, the basis for Marx, Beauvoir, Freire and by extension many more, was arguably proven false before it was put to paper, which is unsurprising since it always was pure speculation. If you try to apply the dialectic to solve problems, you can easily find yourself spreading errors. Methodologically speaking, it is basically meaningless, since the ideal of synthesis has several meanings, including opposite ones. In short, the dialectic has been held in much higher regard than it has any right to. I therefore offer a case against it.

This is not a mere negation that can be fit into the dialectical pattern. The dialectic remains useful for a couple of things, as I have demonstrated in the cheat-sheet series. At the very least it is useful in understanding left-wing and continental philosophy more broadly, and it is useful as a way to organize an argument. There may be more value to it, still. However, it is certainly not a respectable theological replacement for previous theologies, nor is it present in everything. Its failings may be to blame for a lot of recent insanity.

While I won’t compare it to other theologies, I hope I can convince you of this by the end of this script.

The Case against the Dialectic

With Hegel’s introduction of the dialectic to the list of synthetic a priori, a lot happened. First of all, he introduced a process to a list of assumptions about constants, which shakes it up a lot, not least by sneaking in “certainty” about causality through the back door, because it “makes sense”. Note that what makes sense depends on what you already believe. Second, and even more importantly, it is not at all clear that the dialectic lives up to any standard. In the real world, or in ancient stories with significant impact.

In the story of Exodus, you have the archetypal conflict between Masters, the Egyptians, and the Israelite Slaves. One would expect it to present a great example of the master-slave-dialectic. However, it matches neither the master-slave-dialectic or the greater dialectical pattern. The story starts after the Israelites entered Egypt as family to the regent-lord, second only to the Pharaoh, and had prospered in the land. Generations later, the regent Josef had been forgotten, and so a Pharaoh rose who did not remember the hero Josef. Therefore he did not regard the Israelites as friends, and wanted to ensure that the Isrealites would not join their enemies in war against them. With no reported signs of resistance from the Israelites, this led to a system of forced labor which eventually went so far that it qualified as genocide. It lasted until Moses came on behalf of God and God’s punishment of the Egyptians for their conduct towards the Israelites made the Pharaoh recognize that it was not worth continuing on that path. The Pharaoh quickly regretted letting his slaves go free, but God protected his people against the Pharaoh’s armies, allowing the Israelites to escape the Pharaoh’s clutches.

First, what the dialectic gets right about this: The two sides did not recognize each other as equals or friends, and this led to a system of domination for one subject people to oppress the Other.

However, this came about not because of a novel encounter, but because the people who remembered died, and because the ones who remained in one of the populations feared what the Other might do if not kept in check. In short, they never recognized each other as equals, only as friends, and as the people who were friends died, the differences led the new generations to grow more distant and needlessly - this time - suspicious. This is not a matter of dialectic, but of virtues disappearing when not fostered. The prospect that these virtues and friendships can disappear calls into question the very idea that the dialectic ends in unification into one subject, even in the hypothetical. Why would the entropy of friendly relations cease to happen when people are still involved?

Moreover, in the context of the story God is a separate agent who let it all happen in order to demonstrate his power. An agent who ultimately overpowered the Pharaoh. In addition, nothing in Exodus indicates that Israelites partook in any struggle for domination. And the resolution takes the form of the Pharaoh deciding it was not worth continuing, even out of stubborn pride, not recognizing that the Israelites are the equals of the Egyptians. Moreover, with his near-immediate regret, the only reason the story continued as it did was because God intervened again, ultimately placing the Israelites at a safe distance from the Egyptian army by means of an Ocean. In terms of dialectic you could say that it isn’t done yet at this point, but from this point onwards Egypt is just another country among many that the Israelites relate to. There is no indication that there is even a dialectic here.

We can be charitable and see the story of Exodus as a dialectic because it contains the story of moving from one State, through a period of no-State, towards a period with a better State, as a thesis-antithesis-synthesis structure. But note that in doing so, we still don’t have a perfect fit, and we have also thoroughly abandoned the dialectical model for something that anything discussing master and slave should have accounted for.

The dialectic can be seen in and used to make sense of everything. This is its rhetorical strength. It is vague enough that you can always find something to which you can apply it, a feature afforded to it by the way it can take the form of a situation where something is dominated or excluded as well as situations where nothing is, by how it tries to cover relations between subjects and between subject and object, and by how it is a process that can pause. It is easy to let our biases blind us to all the things we don’t even try to apply it to, even though, if it has any merit in this regard, it should apply. This is what is commonly called confirmation bias.

The dialectic utterly fails the test of falsification as a universal component of the world as it makes sense to us, which was devised to ask if something is a scientific question, a question about objective knowledge. That test has its problems, but those problems are relevant for difficult cases, not for cases as clear cut as this. Adopting the dialectic as a basis for the creation of objective knowledge is a strong candidate for the greatest philosophical mistake of all time, even without considering the idea that the dialectic ends in God becoming real, whatever that means. It constitutes a proclamation of faith, that the dialectic is more real than the world around us, as was made clear by some of the more theologically inclined left-wing philosophers, like Freire.

Seeing Masters and Slaves, 101

You might think I am arguing against a straw-man here, that nobody actually believes the dialectic is as real as or more real than anything else. Certainly, few would proclaim that as their faith, but it is my estimate from years of study and observation that you need to assume that various left-wing philosophers hold this faith in order for many of their arguments to make sense. Moreover, while I stress that I have not myself read Hegel, this faith as such does seem to be Hegel’s major contribution to philosophy, and is required for the mere friction between theory and practice to lead where it is thought to by historicists. I find Freire to be among the most clear in this faith, since he basically outright states that the reasoning behind his project is based on how a relationship resembles the Master-Slave Dialectic from Hegel in Pedagogy of the Oppressed’s chapter 2. With that Freire provides an example of how straightforwardly the Master-slave-dialectic can be applied, with an implied correctness that made my mere objection in class fascinate a lecturer who was a fan of Freire’s work. Let me use Freire as a reference point to show you how simple this can be.

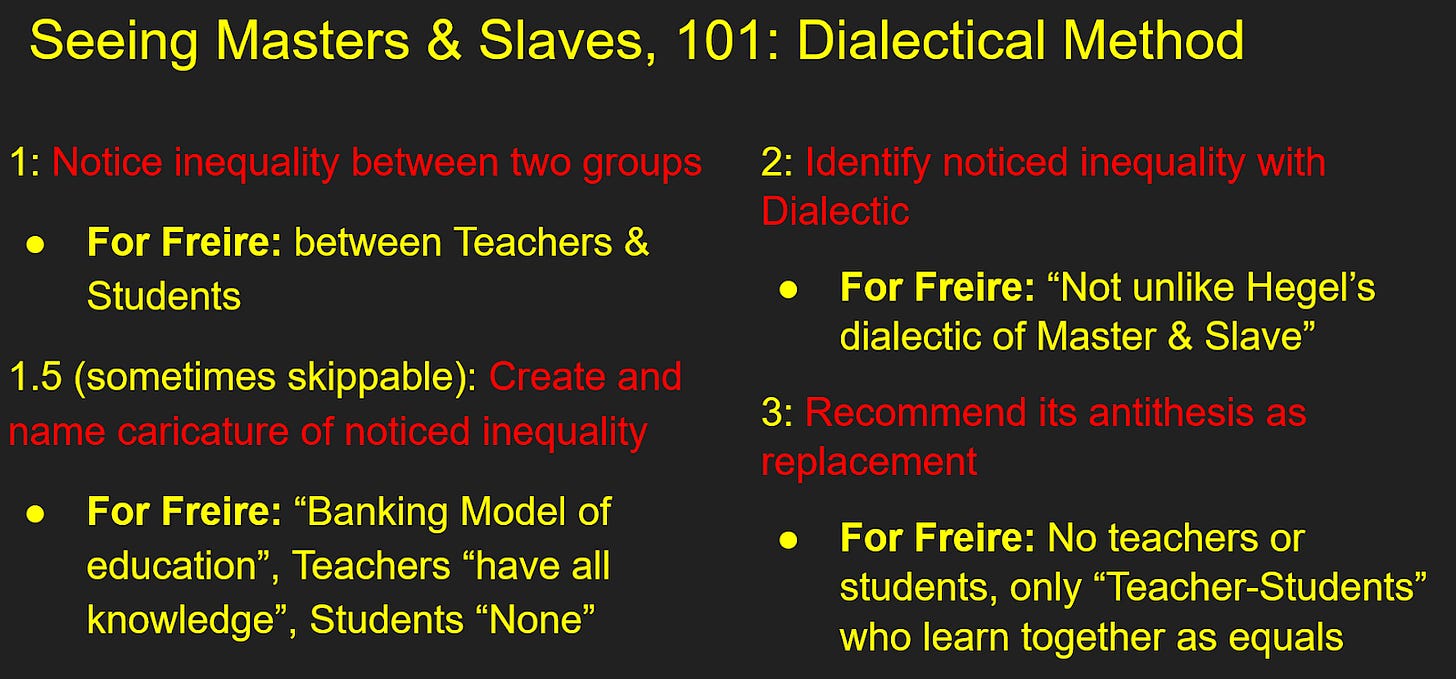

Step 1: Notice inequality between two groups. This is the current state of things, the status quo, or the thesis, depending on how you look at it. Freire noticed inequality between teachers and students.

Step 1.5, which can sometimes be skipped: emphasize, generalize or exaggerate features of this inequality into a caricature which can be named and recognized as such. As a critical theorist you also want it to be easy to condemn morally, so that it motivates Praxis. Freire did this by calling it the Banking-model and characterizing it as a state where teachers are assumed to possess knowledge while the students don’t, which they invest in the students like a bank to get it back on demand during tests, with no care for the students or their actual understanding of the factoids.

Step 2: Identify the named state of inequality as an expression of the Master-slave-dialectic or some variation of it. Freire made this easy for us by explicitly invoking Hegel’s dialectic, but nothing prevents analysis from doing it indirectly by invoking a concept developed with reference to the dialectic, like Marx’s capital. If we were to do this for Freire, we could describe the possession of knowledge as capital in this situation, owned by the teachers and rented out to the students, who lack the ability to capitalize on it.

Step 3: Postulate the antithesis of the named state of inequality as more truthful, morally good or otherwise necessary. For Freire, this took the form of advocating that education should treat both teachers and students as “teacher-students”, who all learn collectively through dialogue as equals. It is also what you see in the end-state of the dialectic of history, in a perfect state for Hegel and in a non-state with no class-distinction, no inequality, for Marx.

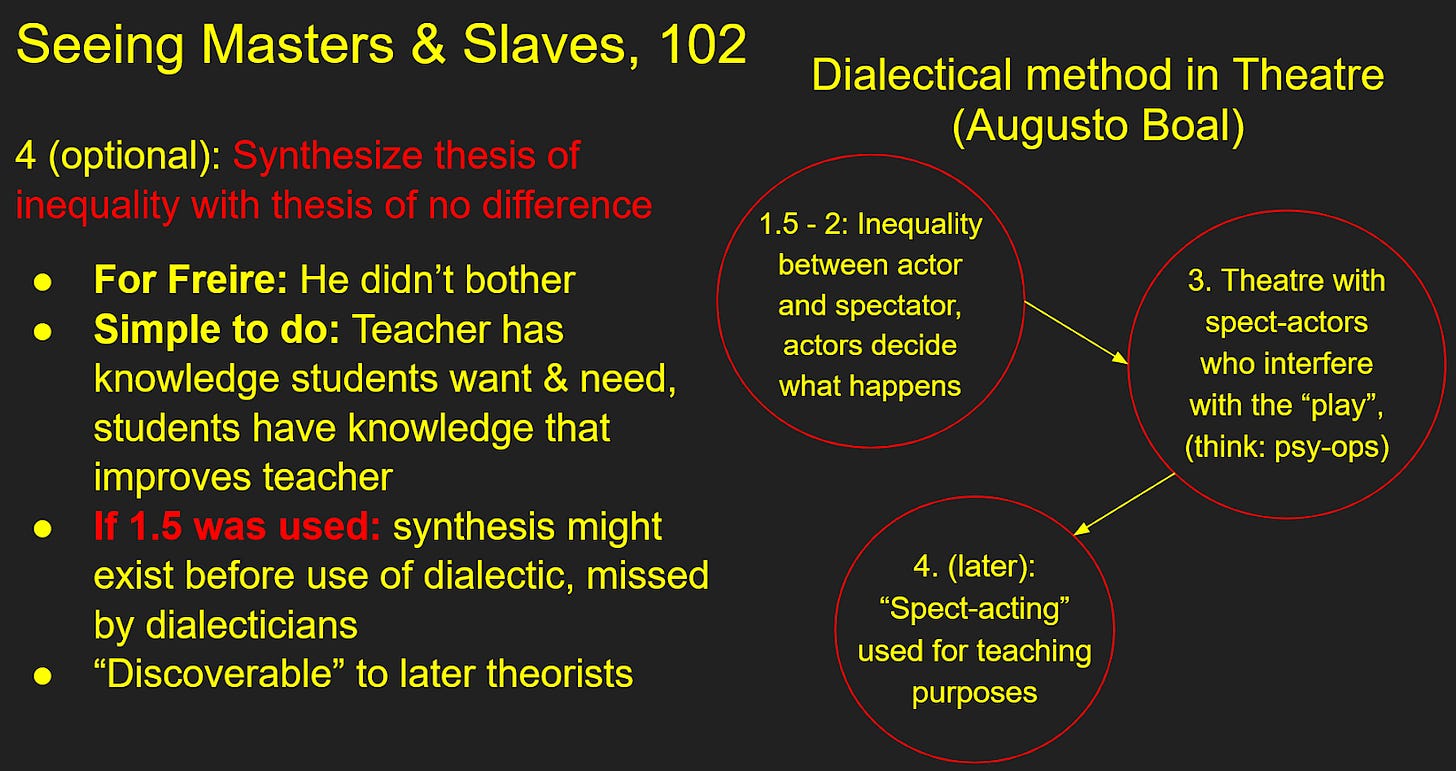

Step 4, which is optional: Attempt to synthesize the thesis of inequality with the antithesis of no difference. Freire did not really do this for teacher-students, presumably because he was looking for a synthesis on a different level, but it is fairly simple: Teachers have some knowledge which the students want, and students have some knowledge that could help the teachers improve. In the event that step 1.5 produced a caricature, step 4 might already be in existence where the dialectic is applied, in which case dialecticians are bound to miss it. If step 4 was not done by the person applying the method, it is likely present in the later theorists who drew on the former.

For a somewhat comical example, consider Augusto Boal’s idea of the theater of the oppressed, or forum theater. He observed the inequality between spectator and actor in theater, and postulated its antithesis, with spect-actors who interrupt and interfere with the play, and are expected and encouraged to do so, whether or not they even know it is a play. This was originally developed as a way to do Praxis while seeming innocent to the powers whose authority was being challenged, but it has since expanded beyond that, into a way to explore how a situation could go down. In that form, its value is entirely dependent on the accuracy with which the spect-actors understand what it is they are emulating.

Jung and Willig

Synthesis is key in the dialectic, and on the face of it, it might seem perfectly fine. But can it go wrong? In the afterword to the cheat sheet series I offered an invitation to synthesize Jung’s self-development and modern Critical Theory, courtesy of Willig. That is, combining the idea that self-development requires acknowledging the parts of yourself you don’t want to admit are part of you because you consider them flaws, with the idea that self-criticism, finding things about yourself to be flaws, prevents you from criticizing the system and is therefore undesirable. Let us have a look at how this could be solved.

We could say this is a conflict between self-criticism and system-criticism, but that would be doing Jung a disservice, since there is no rejection of system-criticism there. It would be fairly easy to apply the idea that we have jungian shadows to societies and systems as well, parts we would rather not acknowledge. A marxist might call them “contradictions”, even if the only thing they “contradict” is how the state presents itself and what is happening makes perfect sense, even to the point where one could argue that the self-presentation, whether it is a caricature based on the master-slave dialectic or not, is the only thing that is flawed. As might be the case with the shadow.

We could say that personal shadows can interfere with system-criticisms, and lead to criticisms that miss the key problem, or complain about good things, echoing Nietzsche’s comments on master and slave morality. Echoing Nietzsche here is entirely within reason, not least since Jung himself developed a lot of his thoughts in dialogue with Nietzsche’s ideas. Since Willig avoids offering a way to adjudicate between criticisms, his analysis is extremely vulnerable to this problem.

However, any standard by which something could be called good is suspect to Willig and the Critical Theorists, since it would benefit some people, the good people, more than others. This applies equally to standards for good things as it does to good criticisms. While some Critical Theorists think that utopia should be proclaimed, it is usually defined by the absence of bad things, since people can agree that something is bad without agreeing on what would be better. However, people can disagree about what is bad, too. Adjudication between criticisms is sorely needed.

It seems we have a conflict here between Jung, discriminating good from bad, and Willig, not discriminating good from bad. A synthesis could then conclude several different things.

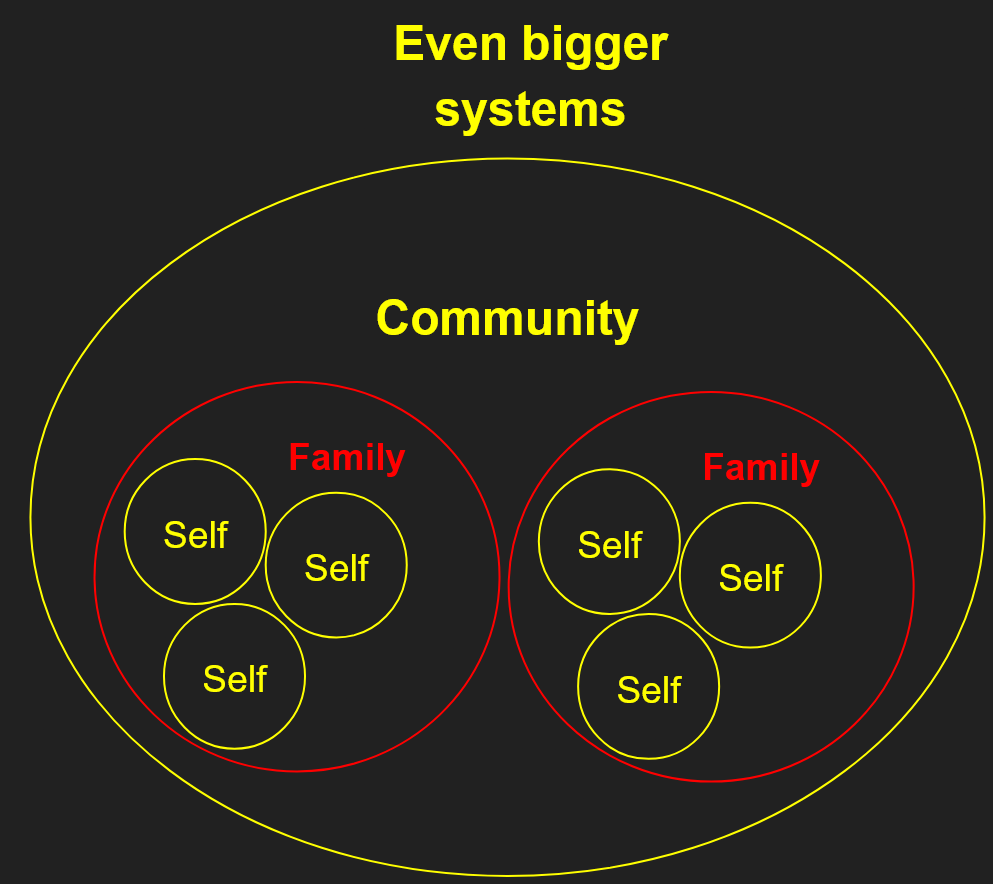

If Critical Theorists accept that adjudication is necessary, they could conclude that they need to discriminate good criticisms from bad criticisms but encourage all criticisms. That could include self-criticism as well. With this solution we would still need a way to determine if a criticism is good or bad. It could be bad if it supports a system. A system could include different levels of analysis, including individuals as well as states, in a nested model of systems within systems. If it includes both, then supporting a system on one level might not support a system on another level, thereby providing no guidance on how to respond in practice. When should one level be prioritized over another? Should we look to change the smallest unit of analysis, the greatest, or something in between? Should it depend on the topic? On what is reasonable, or something Critical Theorists are less suspicious of? And if so, on what?

Comparing this to examples like Marcuse’s treatment of tolerance, it seems likely that Critical Theory would default to its truth-question for adjudication. What is true? Whatever contributes to a successful praxis to end oppressive systems. For Marcuse, his treatment of tolerance was covered earlier. Everything from “the left” should be tolerated. Everything from “the right” should not be tolerated. If it is possible for people on the left to have shadows like everybody else in a Jungian analysis, there is ample room for that to come out with such self-serving conclusions. It amounts to little more than “if I like it, it is good”. But then: Why do you like it? Can you be honest with yourself about that? Would people punish you if you were? Is that a problem with the system, or do you think it is appropriate, deep down? In the end, are you a Nietzschean master playing the slave? Is not that very act contributing to an oppressive system where you benefit in place of and on behalf of others? Or have you just decided that for now, you can decide both what an oppressive system is and what successful praxis means?

Which Synthesis?

The point of this section is to show that synthesis is not one thing, and that there is no “one” result from it either. The “solution” I proposed above to the conflict between Jung and Willig left us with questions of what to prioritize and when, if we accept that both individual and system criticisms are important. We could also say that either is flat out wrong. If I say I am great at football, you object that I am terrible at football, and I explain that I meant that I was great at its rules, it can still turn out that I don’t know the first thing about the rules.

We are rarely comparing exact opposites. This is not “ + 1 - 1 = 0”, and that is not much of a synthesis. If you start with two ideas and you attempt to synthesize them, elevating the ideas to “a higher level”, you might make them make sense together. You could also easily have preserved the errors of both, rejecting what either of them actually got right. If errors are preserved through the dialectic, further syntheses can easily make you more wrong rather than more right.

To make the issues with Synthesis even more apparent, consider the following. I will list three things that are notably different but which all could be seen as synthesis. That’s a problem if you agree that these differences are significant to the point where synthesis ceases to mean much more than that “more than one thing exists”. I have purposefully chosen examples that are more removed from contentious politics, but I hope that these examples remind you of, for example, the way hegemony and discourses were found important, the conflict before intersectionality, or the demands Marcuse wanted his New Man with his New Sensibility to make.

1: The case of dark matter and dark energy. Einsteinian physics are amazing, but fails to explain everything we observe, of both universal expansion and the pull of gravity. To explain this, not least because the model is astoundingly accurate, the physics are assumed to be correct, with the addendum that invisible, hence “dark” matter and energy exists and should be added into calculations. Here, synthesis means that the theory is used to infer the importance of something new which makes it fit the data. Sometimes, the inferred things are even found, like the Higgs-boson.

2: Einsteinian physics and quantum physics. For almost a century, these two models of physics have coexisted, even though physicists will tell you they are incompatible. The tentative solution - as far as I have understood - has been to use either where it works better than the other. This conflict has been resolved with the observation that both theories work well for some things, while physicists hope for a grand, unifying theory, which makes them work together. Here, synthesis would mean such a unifying theory.

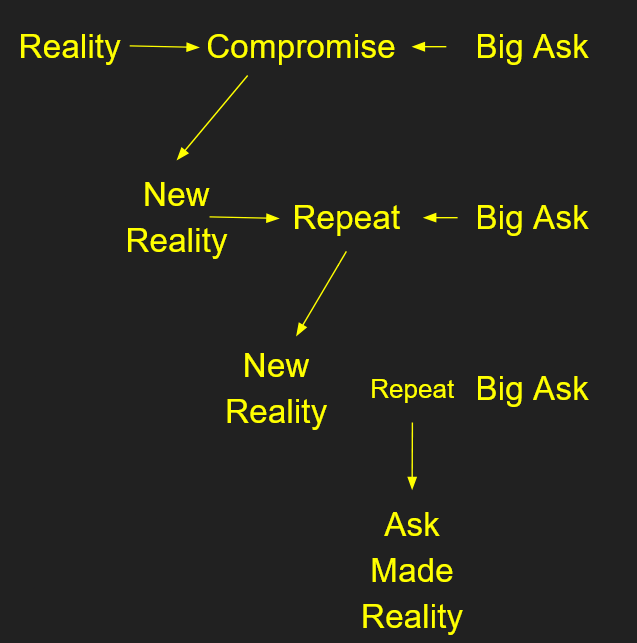

3: A big ask. In finance and politics you will sometimes hear of this trick, in which you, trying to get what you want out of a deal, ask for way more than you could possibly expect to get. This sets the stage for haggling, in which a compromise is eventually reached. Since your starting position was so out-of-this-world, any compromise reached is going to bring reality closer to your big ask, in a way that is easily illustrated as a synthesis. If done repeatedly, with the same big ask, it might not even look as outlandish by the end. Here, synthesis means changing reality according to a theory, that is, the opposite of the first example.

Suppose you want to apply synthesis to something. If synthesis is to mean all of these things, who is to say which it means and when? Is there not tremendous risk of applying the wrong - even the opposite - kind of synthesis to that which would be appropriate? There is a fourth example I could give, which I think is the most damning of all these.

4: Newtonian physics and Einsteinian physics. Newton’s model for gravity has a lot in common with Einstein’s model in terms of results. Not at all in terms of method, where Newton is far simpler. Einstein makes up for its lack of simplicity with far greater accuracy and explanative power, not least because it is accurate where Newton is, as well as places where Newton isn’t. As a result, while Newton’s equations are still used where their inaccuracies are insubstantial, Einstein’s method and theory is what has been slotted into the bigger picture when scientists try to explain how things actually work. Newton’s model was an earlier attempt at explaining what we saw, how things fall down as well as the movement of stars and planets, but it has been completely supplanted because Einstein’s methodologically contradictory model does all the same things and more.

In this conflict between competing theories, synthesis could have meant adjusting Newton’s model, like early astronomers struggled with epicircles to explain why the planets moved in such strange patterns rather than perfect circles around the earth. It could have meant using them both without granting greater authority to either while we await a unifying theory, as though Newton’s model held a candle to Einstein’s in anything but ease of use. It could have meant seeking a way to change reality to better align with Newton’s model, if we had any idea of how to do that and thought it worthwhile. Ultimately, synthesis makes no sense with theories such as these, which seek to explain the same thing in different ways, when one of them just does it better. The only thing even reminiscent of synthesis here is that in the greater context of these models being used by humans, the practical reality, there are times when we find ease of use more important than accuracy, and can make informed decisions about that.

Seeing that Synthesis is so broad and holds contradictory meanings, we have reason to recognize it as an equivocation. It equivocates at least three different things, as we have seen in the examples, while also offering an excuse to not worry about contradictions, in that they work themselves out over time. In that left-wing philosophy has built on this idea of synthesis, having been persuaded by what appears to have been mere rhetoric form Hegel, it has had over 200 years to accrue and spread errors. With that in mind, it is no wonder when it reaches questionable and contradictory conclusions. To offer a novel example of that: in intersectional critical theory, where identities are imposed by a power-structure through oppression, it is acceptable to switch gender identities, to be “genderfluid”, but it is not acceptable to switch racial identities, due to separate developments in the more specialized critical theories of gender and race. As a result, intersectional critical theory is itself a power-structure which imposes racial identities.

A defender of synthesis might object to the fourth example, noting that with Einstein’s physics historically following Newton’s theory, we have a dialectical development where our theories are approaching a perfect fit with reality. This is true, if you only look at the models’ respective explanatory power. If you also look at how the models approach it, there are substantial differences in method, with the main reason for their shared accuracy being that in our local space the space-curve is negligible. Admittedly this lines up with Einstein’s model being the same model lifted up to a higher level where more factors are visible, as would also be the case with a grand unified theory; I don’t want to come off as saying nothing dialectic-like exists, since it is a useful way to understand a number of things, left-wing philosophy chief among them. Even so, in discussing how to apply the dialectic, this similarity misses the point that synthesis can mean any number of things to the point of being meaningless.

I must also reiterate: It is very easy for a synthesis-based perspective to spread errors. Seeing the general superiority of Einstein’s model as a sign of domination could lead this line of thought to champion Newton’s model and argue that it should be reinstated as an equal to Einstein’s, which would work until the Newtonian model’s faults become apparent, or worse yet to try and combine the theories, which makes no sense. The same could be said for modern medicine contra homeopathy, which treats problems with a tiny amount of the cause of the problem plus a lot of water. As homeopathy goes, the general idea is that the more water you add, the more potent the medicine. Meanwhile, when applied to the history of models like Einsteinian and Newtonian physics, the meaning of dialectic has been diluted to the point where adding the tiniest amount of anything to anything else is now synthesis, whenever you learn something new, even if it is wrong. This is a far cry from the union of supposed equals, as in the master-slave dialectic, or Marx turning Hegel “on his head”.

“Dialectical” Relationships

Thus far, the idea of dialectical relationships might appear to be unscathed. With the long list of caveats above, such as that the dialectic of master and slave was falsified before it was thought up, you can say that. The term is applied to all master-slave relationships, broadly construed, but it also applies to the hermeneutic circle, with the idea that a change in how you understand a part of something can change how you understand the thing it is a part of, and any situation where you have two things that depend on each other in some way.

Some things depend on each other for their contents, that much is true. In dialectics, this seems to be thought about everything. In the hermetic traditions which inspired Hegel, Alchemy among them, you will find the idea that God made humans in order to get to know himself, and Jung has gone a long way towards explaining one of the most confusing books in the Bible by assuming this to be true in his Answer to Job. Youtuber Max Derrat covers this in more detail. In essence, the idea is that you can’t know yourself, regardless of what you are, without an Other to compare to, something that is not you. According to this hermetic tradition, God therefore needed to make something that is not-God to become a better God. By the time of Marx’s more philosophical works, this idea was imported wholesale to all of us. It is, in fact, the reason why this tradition seeks to do praxis: To change the world in order to work out our contradictions, to really know ourselves, to understand the whole and how we are, in fact, creators, and that in this we are equal. That in turn is why we should work together to bring about the perfect union of ideal and reality, where everyone is at one and in harmony.

If this sounds religious, that is because it is. It is certainly not all mere facts. We know for a fact that some things depend on others for their contents, like left and right in a given country. We know for a fact that we require resources, like food and water, to continue living. That is not a dialectical relationship, except insofar as a change in food supply causes a change in our lives, but you could at least argue that. More fundamentally, we now know for a fact that this kind of harmony is physically impossible. Not mere religion, then, but a cultish pipedream, which should not be held in any higher regard than the religions it condemns as false teachings, the “opiate of the masses”, since they at least can be coherent. Let me explain why before I wrap this up.

The Frame Problem & Constructivism

As scientists and computer engineers attempted to make programs that could see the real world, it quickly became apparent that seeing was a lot harder than we thought. If you take a picture, you see it and you probably think about the objects you can see in it. Maybe a house, maybe a tree, maybe some people and how they are dressed. Now, if you put the same picture under a microscope, do you still see the same objects? What if you didn’t just use a microscope, but an electron-microscope, capable of seeing molecules? What would strike you? This is a constant problem for anyone trying to reverse-engineer vision: What level of resolution is appropriate and when? It is made all the worse by the fact that it depends on what you are trying to do or see. It seems easy to our brains because they have evolved to solve it automatically for at least hundreds of millions of years.

This problem does not just apply to vision. It was also noticed in reading by the poststructuralists, asking “what is the appropriate context to read this in”, with answers like Derrida’s famous answer that there is nothing that does not have a context, often clumsily translated as “there is nothing outside the text”. Derrida and those of a similar mind drew from this that you choose whichever context suits you, as does everyone else, and that if somebody chooses a context which does not suit those with power, they use that power to punish it.

You can ask what the appropriate way to sort information is in general. It should be clear by now that this also applies to hearing. In short, it applies to all sensory information. This is known as the frame problem, and some, known as constructivists, suggest that our brains use most of our early years to figure out how to see, hear, and so on, and that this is a big reason why it is so hard to remember the first years of your life; Your brain could not make sense of it yet.

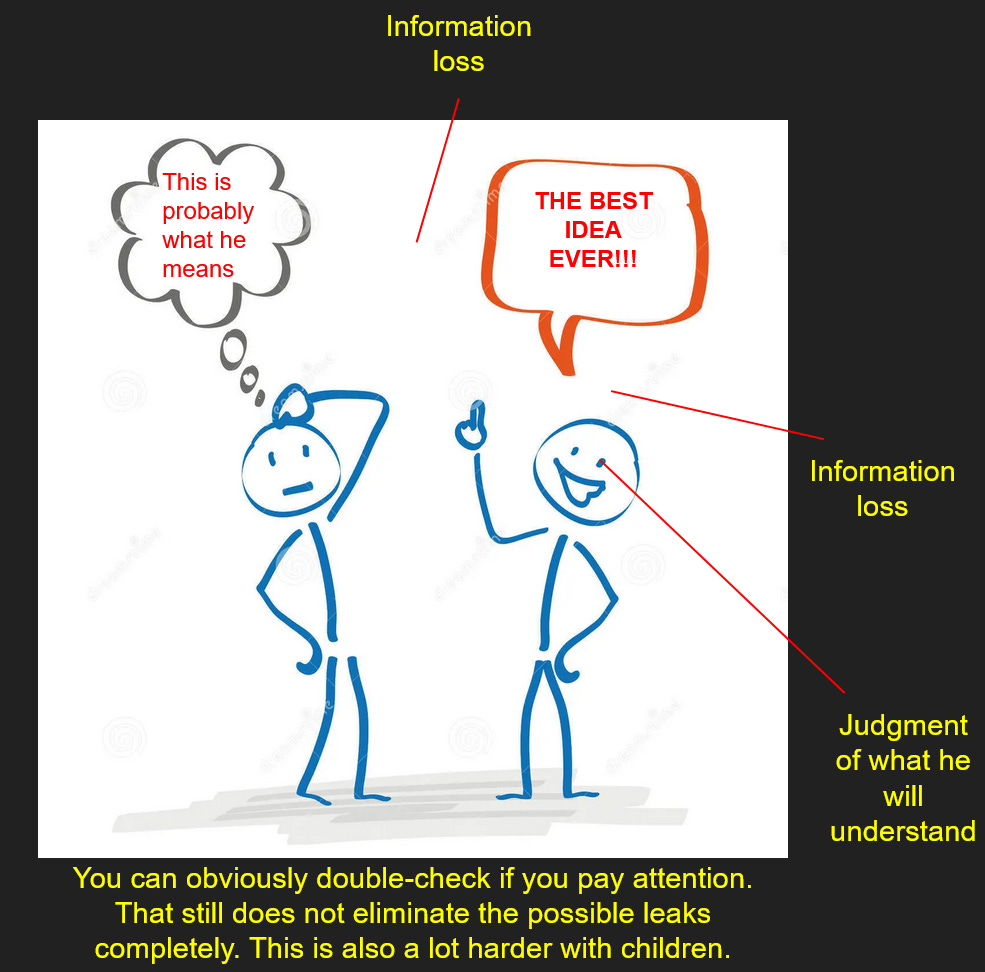

Whether or not constructivists are correct about our first years, they have a point, and that point extends to language. When interpretation is so difficult, it comes down to our built-in systems of pattern-recognition to work out what patterns are noteworthy and when. We must be able to recognize where one word ends and another begins before language comes to mean much at all to us. Then, our brains have to employ a similar construction-process to work out what any one word means, and what other words and gestures change its meaning. This could be things like a sound (once sounds can be distinguished) ending on a higher frequency than it starts, which usually indicates a question in human languages, or a lower frequency, which usually indicates an assertion. You build your own individual understanding of what every single word in your vocabulary means.

As we work out these meanings, we employ built-in, that is, evolved systems of pattern recognition. Everything that evolves is subject to natural variation, so your pattern-recognition might pick up on details mine would miss, or vice versa. A second level of variation comes from the fact that people in different places and different times use different words. These two levels of variation make it so that if we were to draw a circle around all the words I think mean the same as a given word in a given context and a similar circle for yours, there is a reasonable chance we will disagree about at least a few edge cases, though most of the synonyms we will probably be in agreement about, that is in the overlap.

Now imagine that you try to communicate an idea to me. You have a rough idea of what you want to say, and a rough idea of what I understand already, so if you have any sense, you will try to use what I already understand to explain it to me. You will also be taking an idea from your mind, translating it into words you think are appropriate and which I will understand, and offering that to me. If I pay attention, which I don’t have to do, I can probably recreate the idea in my head from your output, with some minor variations from edge meanings of words that have slipped us by, and maybe a connection to something I know of which you don’t. This is to say there is likely going to be an information leak even when I pay close attention and you do a good job, where I fill in the blanks and might do so incorrectly. This is basically the same as genetic mutation, but probably more frequent. Now add in the possibility that I might not be paying that much attention. That would mean more blanks to fill in. Now factor in that every new generation brings new minds that need to have the brilliant ideas inserted into them for the harmony to continue. At scale and over time, the information leaks make that essentially impossible.

As an aside, since the frame problem necessitates a system that filters information in our minds, which is most efficiently explained by evolution, it also invalidates social construction as a stand-alone theory. Without such systems, which would mean it is not just about power, it has no explanation for how children can ever learn any language, making social construction impossible.

Closing Words, Natural Selection is a humble Alternative

In the end, the world is complicated. We try to make sense of it, and we “live in” the world as it makes sense to us. But it does not make sense to any of us in exactly the same way. Sometimes, what makes sense to us is wrong in ways that kill us. When we can also communicate about how things make sense to us, we have everything we need for natural selection to operate on how the world makes sense to us.

Let us go back to Descartes for a moment. Philosophy wants to build on certainty, but we can only be sure of our own existence. Then we have things we can’t help but to think, synthetic a priori. They don’t offer certainty, but they offer some semblance of confidence; At least it makes sense. If the sense-making is simulated by brains in living beings, natural selection is operating on several levels. That should make it line up. What seems right can only survive so long as it is not too wrong. However, it can take time to discover this, and we gamble our lives on it. What seems right can still be too wrong to survive on its own.

There is a good case for the dialectic as an aid in structuring thoughts. Even though I think a lot of things are like the dialectic in some ways, I do not think the dialectic is one thing in any meaningful sense. Instead I think that seeing it as one thing is a mistake. It is a fine tool in the toolkit to help us make sense of the world, but applying dialectics to everything makes no sense at all.

Trygve Taranger is an autodidact software developer, data scientist and musical composer with a Master’s degree in Media Practices. While in university, he accidentally found himself learning about Critical Theory every single year in most of his courses. Trygve is most active on X as @CuriousnTT, where he explores different ways to think about things.

Sources for the whole project:

John Vervaeke’s Awakening from the Meaning Crisis series on Descartes, Kant, Hegel.

Hans-Georg Moeller’s (Carefree Wandering) videos on Hegel, Kant and Nietzsche

Marxists.org’s dictionary, which has useful explanations of various terms, including truth, as seen from the perspective of marxist left-wing philosophy.

Marcuse’s Repressive Tolerance.

Chapter 2 of Paulo Freire’s Pedagogy of the Oppressed, which really clued me in to how fundamental the dialectic is to left-wing philosophy.

For what might be controversial claims about Critical Theory I refer to Finn Collin and David Butz Pedersen’s paper on the Frankfurt School and Science and Technology Studies, which you can find here: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/02691728.2013.782588

James Lindsay’s New Discourses-podcast, various episodes.

Wikipedia on Kant, Levinas, Foucault and Derrida, structuralism and post-structuralism.

Helen Pluckrose and James Lindsay’s Cynical Theories. (Books like this one are particularly useful for the topics they cover, since they provide an overview. In spite of the name and cover illustration, it mostly covers postmodern theory.)

Agora journal for metaphysical speculation, 2012 special publication on Habermas, featuring an article by Willig and several that discuss Honneth. Sadly it is written in Norwegian, but many of the articles are translated. From German, Danish, etc.

Zarathustra’s Serpent on Nietzsche.

Jordan Peterson’s Maps of Meaning: The Architecture of Belief on Jung and Alchemy.

This blog post on Alchemy and the Wheel of Time: http://13depository.blogspot.com/2002/03/the-refining-principle-alchemical.html

C.E. Evink’s On Transcendental Violence, covering Levinas’ and Derrida’s very different uses of the phrase. For Levinas it is what the Other does to you by interrupting your life and plans, and for Derrida it is what you do to the Other by categorizing it without asking.

Gert J. J. Biesta’s Beyond Learning: Democratic Education for a Human Future. This book takes this logic for granted near the end of this line, and features a lot of Hannah Arendt’s philosophical work, which basically takes the marxist model of different types of work and adds one that means Praxis without trying to force a specific result. It was omitted here because it did not seem to add that much.

Various books that blur together in my mind after 7 years of research.

Various lectures that blur together in my mind from various people operating on or explaining left-wing philosophy. One of these is my source for Sartre, for example.