A Cheat Sheet for Left-Wing Philosophy

Part 1

(Editor Note: This post is a script from a video series and will be published as an E-Book in the near future. This is only part one. The video is provided but the text and diagrams are below.)

Have you noticed how hard it is to understand philosophers? I know I have. Ever since my mother introduced me to Sophie's World as a child, I’ve been interested in philosophy. I don’t think I was the only one who got the sense that the story kind of fell apart with more recent philosophers. Apparently, particularly German and later continental philosophy is widely regarded as basically incomprehensible. In my own studies, I only ever read primary works by two continental philosophers, Nietzsche and Habermas. However, I paid close attention and tried to reverse-engineer the logic from various lectures and other second-hand accounts. Since particularly the philosophers on the left are openly political, and I have been interested in political philosophy for quite a while, and these philosophers often draw on particular sources, I have found the Hegelian Dialectic to be a useful way to understand them in particular. Essentially, I see the Hegelian Dialectic as *the* Cheat Sheet for left-wing philosophy.

Since this is all second-hand or worse, I don’t claim to accurately present all of Hegel’s, or any other philosopher’s thoughts here, only that this is a nice simplification to use in order to make sense of different philosophers from the last 200 or so years, as well as the progressive movement more generally. I hope for the following to be helpful and understandable to anyone. However, with academic terms in mind, it might still be heavy enough to warrant breaks or reflection on each section before moving on to the next. I hope that by explaining the cheat sheet I can minimize the number of things that surprise you about the basic logic of left-wing philosophy.

While I have tried to keep this short and simple, there is a lot of left-wing philosophy to cover. What started as a plan for a single video turned into a script of more than 30 pages and an estimated 1 hour and 37 minutes speaking time. I will therefore be releasing it in parts. The first part will explain where the dialectic comes from and what it is, and end with a few examples of how philosophers have adapted it. The second will use the dialectic to explain critical theory. The third will cover postmodernism, how it grew out of critical theories and how it was spun back in. The final part will be an afterword with some reflections and, for people who might still struggle with the dialectic, the cheat sheet itself: A shorter summary of what I covered in the earlier videos. In a later follow-up video, I will offer a case against the dialectic, and a guide on applying it.

Part 1

The Dialectic

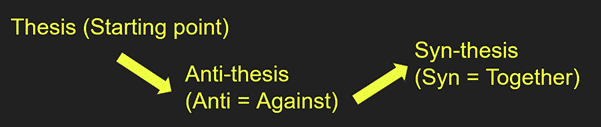

The dialectic is the name of a process in which two things that don’t seem to go together are made into one. The following paragraph illustrates.

This sentence is the dialectic. But it is not complete. It requires some kind of negation of the starting point before the two are brought together into something new. This forms the simplest model of the dialectical process, commonly known as thesis - antithesis - synthesis. As you may have caught on to, then, it wasn’t actually the sentence that was the dialectic, but this entire paragraph.

To make it easier, here is another example:

Person 1: I am great at football. That’s the Thesis.

Person 2: I think you’re pretty bad at football. This is the Antithesis.

Later, after talking about what they meant:

Person 2: Oh, so you were talking about understanding the rules of football, and not about playing it. That’s a Synthesis.

Since the dialectic involves some kind of contradiction, two things that on the face of it can’t both be true at once, the road to synthesis usually involves a change in how we think about the topic. In the paragraph-example, the starting thesis, that the sentence is the dialectic, is expanded to be about the paragraph instead. With the football-example, it turns out that they meant different things by “football”, with one referring to playing the game and the other referring to knowing its rules. This kind of change of frame for the original thesis is a common way for the dialectic to be “solved”.

It is a generally useful way to organize your thoughts, and is a lot older than Hegel, though it was only formalized in this way fairly recently. I have heard that the names thesis - antithesis and synthesis originated with Kant[1]. Hegel used different words for the process, and applied it to a lot more than the organization of thoughts. Before we get to Hegel proper though, a basic familiarity with Descartes and Kant is required.

Descartes

Descartes is most famous for the statement “Cogito, ergo sum”, often translated as “I think, therefore I am.” This is what he ended up with after doing a thought-experiment, called “radical doubt”. In this experiment, he would reject all knowledge he did not have absolute certainty about. The senses sometimes betray us, so they are not certain. I can imagine that a demon makes math only appear to be certain by hiding that some numbers refer to oranges and others to apples. You get the idea: He was very strict about this. The only thing he was certain about was his own existence.

Philosophers generally want to build on certainty, so this was a major problem. Descartes tried to solve this problem in a strange way, by observing that his doubt allowed him to imagine a being without these doubts, a perfect being, or God. A perfect being could not be imagined if it did not exist, and it would also be fundamentally good. Therefore it would serve as a guarantor of the certainty of math and the world experienced through the senses.

My sense when learning this about Descartes was that there were problems with this logic which undermined its alleged certainty, and you can probably point to some yourself. That is not the point here. The point is what his thought-experiment started. Through it, Descartes became a key figure in the debate between rationalists, who regarded reasoning to be a source of knowledge ahead of experience, or a priori, and empiricists, who regarded reasoning as fallible, just like experience, and therefore deferred to experience, a posteriori.

Kant

Many consider Kant’s contribution to this debate to have marked its end point, about 150 years after Descartes' thought-experiment was published. Kant made the now-established distinction between the thing as I see it and the thing as it is, and concluded that the thing as it is is outside of the world of experience. He also concluded that reasoning gives reliable knowledge, but not of the world as it is. Rather: as it makes sense to us. Subjective experience can become “objective” by being connected to a set of assumptions we cannot help but to make, such as that time flows. The scholarly term for these assumptions is synthetic a priori.

In this view, objective does not mean “true about the world as it is”, but “true about the world as it makes sense to us”. This is a key distinction, since it opens up space for ideas like those of the psychoanalysts, who analyze what people have previously thought, for example about the constellations of stars in astrology, or religion, to see how the world makes sense to us, as a kind of study of human nature. It is also key because “true about the world as it makes sense to us” did not satisfy everyone. The romantic movement took this to mean that reasoning and making more sense constituted moving further away from the world as it is. They therefore largely rejected reasoning, since they wanted to be a part of the world, not just of what makes sense.

Meanwhile, Kant said something to this effect: That the mission of philosophy was to create new assumptions we cannot help but to make - new things that were synthetic a priori. Later philosophers would take this to heart, for our purposes, starting with Hegel.

Hegel and Historicism

As noted earlier, the thesis - antithesis - synthesis structure was apparently coined by Kant, who regarded it as a useful way to organize thought. Hegel essentially made the case for this structure as a fundamental force operating in the world, that at least practically everything followed at least basically this model. His words for the dialectic, in the same pattern as Kant’s, were abstract - negative - concrete. It is meant to describe how things become real.

On the largest scale, this was the idea that history moved dialectically, that history was the story of consciousness becoming God through Reason, of how God is becoming real. If this is surprising, it is worth knowing that one of Hegel’s ways to the dialectic was Alchemy. In Alchemy, one of the major motivations was to make matter, in an older sense than the one we currently understand, into gold, in a broader sense than the metal. We can understand it as making things valuable.

In order to do this, it was thought that the alchemist had to apply the alchemical process to himself, in order to refine body and soul. This was the process of creating the “philosopher’s stone” from the base material, the spirit of the alchemist. In the context of Christianity, the product of this refinement-process was increasingly identified with Jesus Christ. On other materials, they would start with the solid raw material, then seek ways to make it dissolve, then find a way to make it solid, once again. They start as who they are, then dissolve themselves confronting a negative, before rebuilding in a better state. Do this enough times in the right ways, and you would be the philosopher’s stone, capable of making anything valuable, or God on earth.

We can understand this large-scale dialectic as consciousness as such undertaking this alchemical process like the alchemist, until the end point is reached. Then it looks back on how it got there, and understands it all as critical for it to reach Godhood. Critical is a common translation of Hegel’s Notwendigkeit, but an alternative is “necessary”. Critical is used in much of the philosophy that followed, under the name “Critical Theory”, where it constitutes a play on words; It is “critical” in other senses as well. Nonetheless, the dialectic can be understood as “His, God’s, story”. Variations on this idea are known as historicism, with varying degrees of reference to the dialectic.

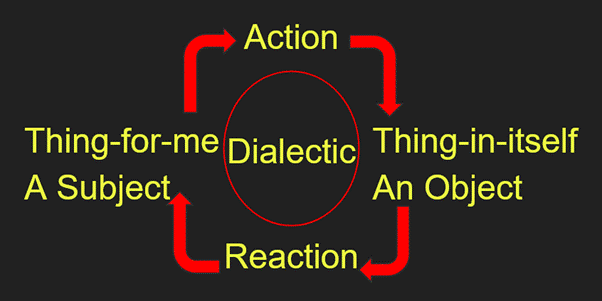

The Dialectic as Hermeneutic Circle

More concretely Hegel’s take on the dialectic was a response to the quandary of romanticism. Do we really move away from the world by trying to make sense? No, Hegel argued, because our subjective experience is in a dialectical relationship to the world. The subject, as it was, interpreted and acted on the object, the thing in itself, thereby changing both. This could be viewed from either side: With the subject as negative to the object or vice versa, but either way the encounter with the negative eventually transformed its Other, a term we will come back to, into a higher state. Thus, one could embrace reason without moving away from reality, by doing things in reality.

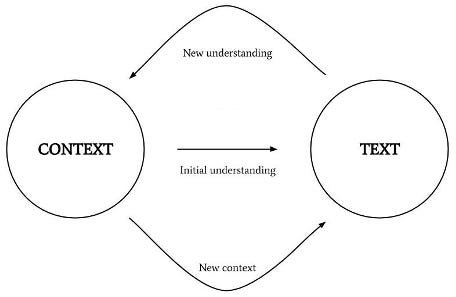

In this respect the dialectic is more like a circular model indicating mutual influence, which is something it has in common with the Hermeneutic circle. In hermeneutics, this circle is used to illustrate the way a reader understands a text based on the pre-existing, abstract understanding. Through engagement with it and its occasional negations of the pre-existing understanding, the understanding becomes more concrete. This circle is also used to illustrate how a line in a text is understood in relation to the greater whole, the context.

The hermeneutic circle is a helpful visual aid in understanding Hegel’s dialectic between people, too. Simply replace “text” with subject and “context” with other subjects. In the hermeneutic tradition, the notion of text eventually expanded to encapsulate everything, as it is experienced as carrying information that invites the hermeneutic and - as you can see - dialectical process to continue.

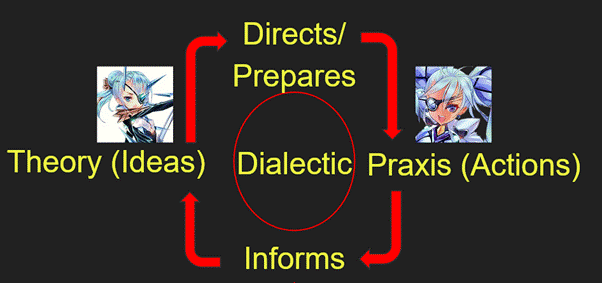

Theory and Praxis

Seeing the Hermeneutical Circle as a model that highlights certain features of the dialectic, we can understand what is meant by Theory and Praxis. Understanding in the hermeneutical model is Theory in dialectical thought. Praxis is what is done to or in the world because of Theory. When working properly, Praxis continuously informs and updates Theory since, unlike Theory, Praxis is limited by the context of what is possible. At the same time, Theory directs Praxis, by detailing what Praxis can look like, anticipate and respond to.

By engaging in Praxis as well as Theory, philosophers after Hegel would seek to be a part of the world, as the romantics desired, without giving up on Reason. It is common to think that Theory and Praxis requires a conscious goal, potentially distinguishing it from general-purpose-modeling, but these terms are relatively loose, so it is not a given. One might also ask what distinguishes a conscious goal from an unconscious goal, but I think this largely misses the key distinction here, which I think is between descriptive and prescriptive use of the terms.

Read descriptively, Theory and Praxis are things humans do all the time, anyway. In this sense, it is not something you do because you want to be a part of the world, but something you do because there is no other alternative, and you have to do something. In this reading, there is no difference between a model and Theory, and it merely describes the relationship between our models and life, at most providing a language through which philosophy can speak to this - if we follow Kant, inescapable aspect of life.

Read prescriptively, Theory and Praxis can be avoided. This seems to be how it was coined in the Hegelian tradition, as something that is necessary to work out contradictions in one’s own consciousness, which specifically transforms social life. In other words, if it does not transform social life, it isn’t Praxis. And you should engage in Praxis because Praxis is what distinguishes humans from animals, precisely because it is conscious. This is how the term was picked up by Marx, among others. The claim that Praxis is uniquely human may be found in both descriptive and prescriptive use, but that it has to transform social life to be Praxis is specific to the prescriptive reading.

Finally for this topic, we may note that the prescriptive sense of Theory and Praxis is analogous to the alchemist pursuing spiritual refinement by applying alchemy to himself. Praxis is the catalyst for spiritual transformation into higher forms. If you hear people talk about a need to “do the work”, prescriptive Praxis is what they are talking about.

Preamble for the Master and the Slave

Hegel wrote a famous passage about what happens when subjects meet that has since been termed the master-slave-dialectic. Unfortunately, the ambiguity of Hegel as a writer shines through, and speaking from personal experience, even the wikipedia-entry on this passage is close to incomprehensible. There were years between when I first looked at it and when I started to work it out. With help from video games, obscure academic passages and literature about Habermas, I now consider it key to a lot of what followed. Understanding it as I do, you can summarize the key contribution of thinkers like Derrida as simply as this: The master-slave-dialectic applied to paired words like man and woman, normal and abnormal, or presence and absence.

Before I go into what it is, you may recall that for Kant, experience could be transformed into objective knowledge about the world as it makes sense to us by connecting it to assumptions we cannot help but make. This remains the case with Hegel, with a caveat: It is temporary knowledge, as it goes into the dialectical process and continually co-creates the next things that can be known as things are brought to higher levels. Moreover, in Hegel’s model, which also draws on Rousseau’s thoughts on democracy for the general will of the people, subjects who recognize each other as equals effectively become a single subject. As a subject, they will essentially be on the same page with regard to temporary knowledge, and will have the same “general will”. Therefore, they act as one.

That many subjects can “be” one subject is immediately important, since the master-slave-dialectic concerns the encounter between two subjects. Definitionally they do not recognize each other as equals, therefore they struggle. That one subject harbours one “general will” is not immediately important, but it ties back to the dialectic at the greatest scale, as once all subjects are one, it will be God by virtue of its general will. That this was thought to be mediated by reason points forwards to the critical theorists, and a lot of what developed in their wake, which we will return to later.

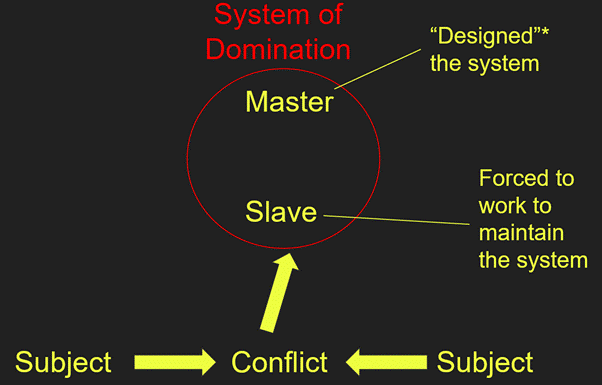

Master and Slave

The struggle between the two subjects can go on for some time, but sooner or later it comes to a close. If they still don’t recognize each other as equals, one will come out the victor, and be put in position to dominate and otherwise exploit the loser. These are generally referred to as master and slave respectively, but oppressor and oppressed works just the same. With that, the connection to much of later left-wing philosophy should already be made clear to some, but there is more to this dialectic.

The master subject enthralls the slave, forcing him to function in a world built by and for the master. This initiates dialectical processes which cause the slave to create and attain knowledge of the master’s world, while simultaneously experiencing the world from the position of slave, serving not only himself but also another master. This makes the slave learn not just of his own position and what he requires, but also what the master requires, and gains him an insight the master cannot, or will not, get.

At the same time, the master subject is in position to decide what is accepted as objective knowledge, and is under no obligation to listen to the slave’s experiences. Thus, through this dialectical logic, the master forces the slave to create and maintain a world for the master’s benefit. The master attempts to turn the slave into an object that can be used to get what the master wants, an object that, after all, is incapable of independent action.

The slave is dominated, but paradoxically the bondage situation leaves the master subject without the experience of the work the slave has to do in his stead. Thus, the master is dependent, and in a sense trapped, just as the slave is, though in a much more pleasant situation on the surface, which motivates the preservation of this state of affairs, this status quo; Neither is truly free, and the dialectic cannot continue before they recognize each other as equals. In the meantime, the existence of both subjects in their current form depends upon the other.

Just as in the more general dialectic, it is with the master and the slave. The slave, functioning as the negative component in the dialectic, eventually initiates some form of challenge to the domination of the master. The master, weakened, perhaps to the point of impotence by his former domination, is unlikely to be able to withstand the slave, whose bondage has forced the development of new and deeper knowledge of their situation. The dialectic might turn upside down in the ensuing revolution, putting them back in a similar situation. And so it goes, until they finally see each other for what they are.

When they finally recognize each other as equals, the dialectic continues, and the abstract master and his negative slave synthesize into a new subject, ready to initiate the process again. If the new subject is sufficiently wise, it might skip the failure to recognize its equal in the next dialectic, and the delay that arose from the period of domination. This wisdom is, essentially, what left-wing philosophers have inherited by following Hegel, understanding everything as a dialectical process and regarding this as something that is as true as the flow of time. By connecting experience to the dialectic, it now becomes “objective knowledge”.

The Ethic of Pure Reason

The notion that many subjects can effectively become one might come off as strange. It makes more sense with a little more knowledge of Kant. The ethical dimension of Kant’s work forwarded the proposition that in order to be ethical, moral actions must not contradict each other. As with the rest of his work, Kant approached ethics by looking for something that we cannot help but believe, for good reasons. He came up with several formulations to the same effect: Act based on imagined rules you could want everyone to follow, all at once. He also argued that freedom, or autonomy, which means making your own rules, can only mean voluntarily following his formulations.

With these formulations, Kant tried to make Reason the arbiter of right and wrong. When people are persuaded to follow his ethic, it is easy to think that their later actions would be compatible, and that they would, in that sense, act as one. The hegelian dialectic builds on Kant’s work in this way as well: Reason is the force that makes all subjects become one, since it avoids self-contradiction. If it is true at all, why would it not encapsulate all possible subjects, allowing them all to become as one? And what is the limit to that if not becoming God?

Hegel the Totalitarian

This logic was powerful and persuasive. It was also a very ambitious project. With the dialectic of history, an immediate follow-up was the question of what the subjects along the way were. Since I haven’t read Hegel myself, I don’t think I should be too specific here. That said, it is widely accepted that he considered the State as the manifestation of the divine ideal on earth. This suggests a view of States as a subject in the dialectic: the concrete, temporary end-result of the dialectic where abstract ideals encounter reality. This also indicates that at one point, the end result would be the perfect State, at least if Reason will produce God.

In a perfect State, where everyone acts autonomously according to Reason in everything at all times, the singular subject will have become God, in the perfect, all-encompassing State, Heaven. All it takes to get there is for everyone to be on the same page. Is it a surprise then, that Hegel is known as the philosopher of totalitarianism? All the same, his ambitious and ambiguous work has inspired just about all continental philosophy since then. I will consider a few examples of them to give you an idea, very briefly.

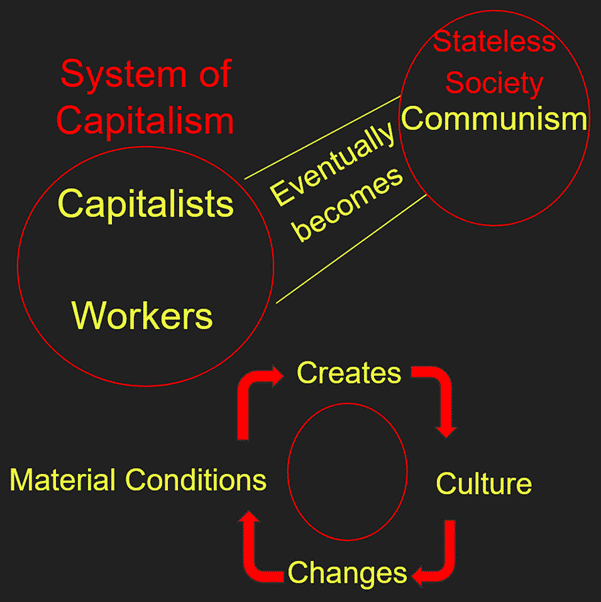

Hegel in Marx

In his work, Marx at one point said he had turned Hegel on his head. This is a simple way to put it. He took Hegel’s historicism of consciousness and Reason, and said it was about material conditions. Instead of culminating in a perfect State, it ends with a global, stateless society. Marx places the dialectic between material conditions and culture, and says that the former plays the role of the negative, that is, it determines when things change. Instead of regarding the state as the manifestation of the divine ideal on earth, he sees a master-slave dialectic between the capitalist master and the worker slave, all around the world. It is still a matter of “necessary” or “critical” developments, which led Marx to describe it as scientific.

Nietzsche and “Necessary”

Nietzsche largely does his own thing, but a philosopher tells me that Nietzsche referenced and criticized Hegel in subtle ways. Most importantly with the observation that it isn’t “necessary”, but more like “possible”, that what Hegel thought inevitable was but one of many ways things could go. Things can still seem inevitable and necessary in hindsight, but that does not mean they actually are. For Nietzsche then, the dialectic becomes a fluke when it moves from reflecting on the past to speculating about the future. With this in mind, his philosophical system of will-to-power can be translated to dialectical terms. Each will-to-power, which is one thing as it can be noticed, for example as an atom or a molecule, constitutes one subject. The wills-to-power collide in a myriad of ways as they sometimes align into greater subjects and sometimes fall apart. In the Nietzschean model, Reason might be understood as one will-to-power among many, and not necessarily the most powerful or able to unite all subjects.

Nietzsche on Slave Morality

Nietzsche’s analysis of Master and Slave morality was probably done as a kind of response to the master-slave dialectic. Nietzsche basically argues that the slaves delude themselves into thinking strength and pursuing what you want are evil, vices. The slaves would speak in terms of good and evil. By contrast, the aryan, meaning spiritually “rich” masters, would look at what the slaves are doing as folly, and would see the world in terms of what is “good for me” and what is “bad for me”. Good and bad, not good and evil. He also saw slave morality as fundamentally destructive, because it looks at what masters do to orient itself by saying that what the masters choose to do, what is “good for me”, is evil. This self-denial, dubbed asceticism by Nietzsche, is what would ultimately give rise to nihilism, that is, the pursuit of nothing. To reiterate: Nietzsche largely does his own thing, even when he references the dialectic. He also both praised and criticized everything, including slave morality, which he thought might have trained people to make and keep promises.

Existence in the Dialectic

In the dialectical view, nothing lasts forever, except maybe the dialectic itself. When Sartre says that existence precedes essence, and that we who exist make a choice in how we create our essences, this can be translated quite simply into this: We exist in the dialectic, and the things we choose to pursue play a role in its future development. Existentialists generally follow the Nietzschean perspective that the specific turns of the dialectic are not “necessary”, except maybe in hindsight. I also got the impression from a lecturer at one point that Sartre reviewed friendship in light of the master-slave dialectic and concluded that friendship between masters and slaves was not possible, or at least, not true friendship. This was because of the power-imbalance between the two subjects.

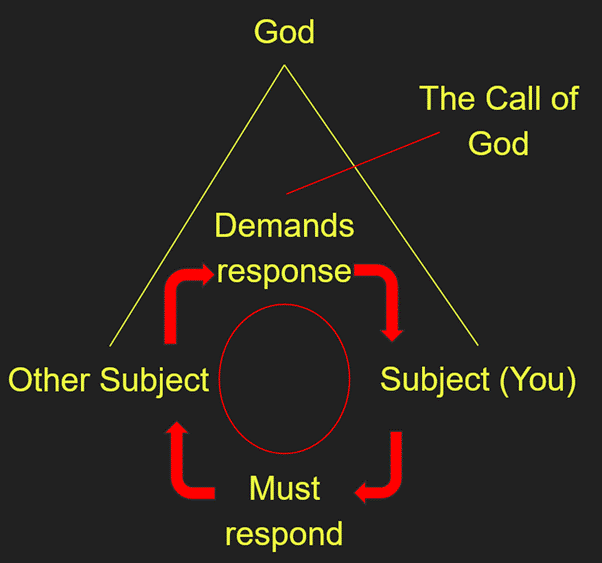

Responsibility and the Other

As we exist in the dialectic, from the perspective of any subject, we encounter an Other. This Other is a subject, or at least, like a subject, taking the position as our dialectical opposite. The Hermeneutic circle may make this easier to understand. The Other breaks into the world as it makes sense to you and shakes it up, and forces you to develop a new understanding with the Other in it. Taking care of the problem posed by the Other, by the antithesis to your order, is an unavoidable and perpetual responsibility.

By responding to the Other in a proper way, many of the more phenomenologically inclined philosophers, with Levinas at the forefront, put the ethical responsibility in the encounter with the Other at the bottom. It is an infinite and involuntary responsibility in this view.

Here, the Other is essentially the closest thing in existence to God, and should be treated with appropriate respect. The Other is also of the same nature as yourself, as dialectical equals. Recall that the dialectic leads towards the realization of God. In the simplest terms, this is the sense in which the subjects in the master-slave-dialectic are supposed to ultimately recognize each other: As equal parts of the whole that becomes God.

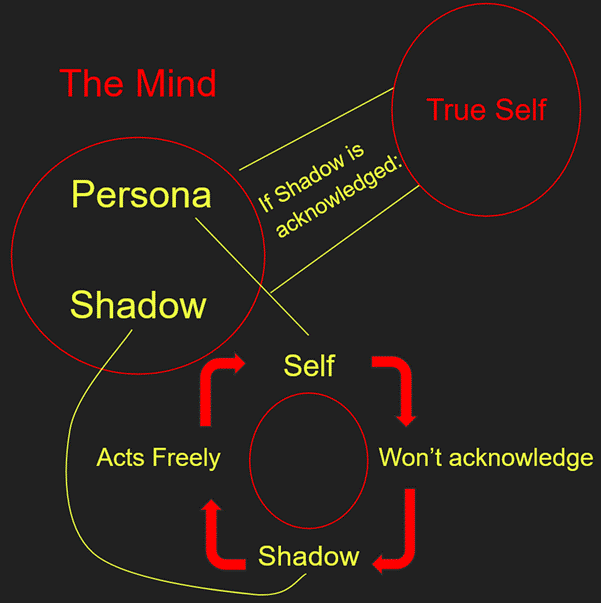

The Jungian Dialectic

The Jungian version of Hegel’s dialectical model is not particularly important here, but I give it a short summary anyway, to show that it reached far, and was applied to a lot of different things in a lot of different ways by a lot of different people. Jung also looked back to Alchemy in his model, so I can’t rule it out that he came to it independently. Nonetheless, you can understand a lot of it through Hegel’s Dialectic.

Jung modelled the mind as consisting of a conscious and an unconscious component. The unconscious is understood as more powerful but not organized, whereas the conscious is weaker, but organized, so it knows what it is trying to do. Common terms associated with these are the mask, or the “persona”, and the “shadow”. The mask is how you consciously perceive yourself and want to be perceived by others, and the shadow is all the parts of you that don’t match the mask. Since they don’t match, you will try to hide and deny the existence of the shadow, which means that you won’t admit to it when you demonstrate the traits of your shadow to the world. Effectively, this lets the shadow act freely in the world, as it cannot be kept in check by consciousness if the conscious mind won’t admit that there is something to keep in check. Meanwhile, Jung sees a possibility for the shadow to be integrated into your understanding of yourself, for the two sides of your psyche to become one. This process is dialectical, and the end product, which is purely speculative, is the “self”, which Jung identified with God.

[1] I’ve since learned that the way they are organized comes from Kant, but not the names. The names come from Fichte.

Trygve Taranger is an autodidact software developer, data scientist and musical composer with a Master's degree in Media Practices. While in university, he accidentally found himself learning about Critical Theory every single year in most of his courses. Trygve is most active on X as @CuriousnTT, where he explores different ways to think about things.