A Cheat Sheet for Left-Wing Philosophy

Part 4

(Editor Note: This post is a script from a video series and will be published as an E-Book in the near future. This is only part one. The video is provided but the text and diagrams are below.)

Part 4

The explanation is basically done with the previous part, and so this part is going to offer some reflections about it and a summary. Before that, well, throughout this series I have called it a project of “reverse-engineering”, and I think it is appropriate to expand on that a little at this point, beyond the definition I’ve pulled from wikipedia. You can think of it as a matter of transparency.

My Process

In a way, this project has been a long time in the making. It started with me as a teen, looking at a puzzle in late 2015 and early 2016. Since about that time, I have looked at people with what is now called a “woke” disposition, and tried to figure out what happened, what led to what I regarded as their broken reasoning and disregard for what I thought were obviously fundamental principles, like freedom of speech. Since I found this puzzle so fascinating, I was particularly interested in any work I could find which looked at the actual works, the papers and books underlining the philosophy I saw, regardless of if it took a side in the matter, knowing as you probably do by now, that left-wing philosophy is generally very political.

When I started at university in 2016, and especially when I got an openly marxist professor in 2019, I found some of these works, or remarkable parallels, in our curricular texts. Therefore, I read them very carefully, argued with said professor and anyone who would join me, and made mental footnotes of basically everything I found curious about the whole thing. Meanwhile, I read a lot of these books. You may have checked out my simplified source-list, but here are screenshots of my physical collection of books. I have not read everything you see, but I have read most of most of them, a lot of them in full and a lot of texts which I never got in physical form. Many of these books deserve more comprehensive coverage.

As you can see, I have brought together a stew of various kinds of information from a time-period of about 7 years. In typically autistic fashion, I have spent several hours out of just about every day devouring information to figure out how this puzzle fits together. What I was looking for was a way to explain what had happened that made sense. This series does not offer that, but I think it offers the next thing to it, if we limit the analysis to philosophy. And the answer within philosophy, which I have explained at some length here, is a philosophy that believes in nothing more than it believes in the dialectic.

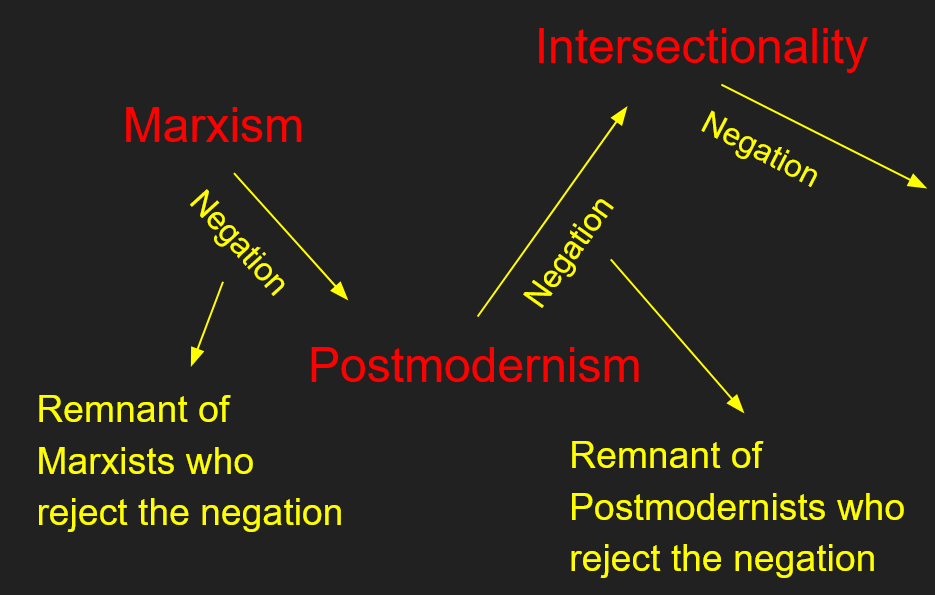

There will always be remnants

This might not strike you as an adequate explanation. I think it is, but it is part of a bigger picture having to do with how culture evolves - which is another topic I have devoted an absurd amount of time to. For this topic, it is probably enough for you to note a simple fact, which reflects on everything I have talked about in this series. Every philosophy which has been able to stand on its own legs - from its own perspective, continues to exist as long as someone still believes in its ability to stand on its own legs. We still have conventional marxists. You may also recall how I noted that Marcuse’s Critical Theory broke off into new things, even before Habermas entered the picture and said that only one of three rationalities was a big problem.

What I have talked about here is but a branch on the tree of philosophy, expanding outwards into ever-greater multiplicity. In feminist Critical Theory, the currently raging war between intersectional, “trans-inclusive” feminists, who have integrated postmodern theory into their model and the more traditional, “trans-exclusive” feminists who reject these ideas, should offer another solid example. This evolutionary observation, that the philosophies keep on living regardless of whether you think they are dead, because somebody still believes in them, might even be particularly true of Left-wing philosophy. After all, a major component of Critical Theory always was to motivate praxis. Motivation implies belief, and belief is not easily shaken, especially when you have a theory of hegemony, or some other form of unfalsifiable saboteur. We can therefore expect a remnant for every turn these philosophies take.

By now you probably have an idea of where I stand with respect to - at least - the excesses of this philosophy, but beyond some subtle jabs and political inconvenience, I hope that this explanation has been sufficiently fair that even those in favor of said excesses can affirm that it is a valuable and effective explanation. But enough about me and the process, let us get to the point.

Afterword: The Dialectic of the Dialectic of the Dialectic of the…

Since Hegel, left-wing philosophy has been remarkably consistent in one thing, and that is staying true to the dialectical process. Even people who don’t believe the dialectic is a synthetic a priori that we can use to create objective knowledge should be able to agree that the dialectical logic goes far with left-wing philosophy. Every step of the way, at least since Hegel, the basic ideas are taken to be correct, even if they contradict each other. This was accomplished through a synthesis. You may recall that synthesis takes seemingly incompatible ideas and brings them together by changing how we think about it. Here, as with the football-example at the start, this was done by reframing what came before, as really being about something else, whether we talk about groups, states, cultures, discourses, subjects, etc.

The goal is the same from start to end. What is more free than an omnipotent force? What is more equal than us all being expressions of this force? All we have to do is realize that this is what we all are, and that the systems we have made along the way prevent people from becoming aware of this, and awakening to their true being. Whether it happens through a state as in Hegel or Honneth or without one as in Marx and Marcuse is of no concern. The key idea is that subjects can and should live together in harmony without judgment for how others do things, and this remains true regardless of whether we, like the postmodernists, are suspicious of all powers and therefore do not wish for all subjects to become one in this harmony, or, like the historicists, we are optimistic about the prospect of mankind taking part in the creation of God in the world. In the final analysis, there is little difference between harmony and being as one. The shared and complementary practices of Praxis, especially in their current forms, serve this goal in one sense or the other.

In the dialectic, there is no such thing as a mistake or mis-step. Everything is part of the whole, and contributes to the future development. It is more important to do something than for what is done to be good, because we don’t know what is good in an ultimate sense anyway, or even if there is such a thing. Even so, Critical Theories have always tried to articulate what the good is in the ultimate sense, even when they turned to negative dialectics, but as you recall, the point is to change the world. As long as we try to change it, there is a chance that when God looks back at his story, he will see what we have done and consider it a necessary part of his development, in short, that he will consider it at all. Bringing the dialectic forwards is all that really matters.

When seeing the dialectic as a fundamental reality, is it any wonder that left-wing philosophers apply it to their own theories? As a result, it makes for an excellent format for simplification. Now, for a summary based on the dialectic. This is the dialectic of the development of the dialectic in left-wing philosophy.

The Cheat Sheet:

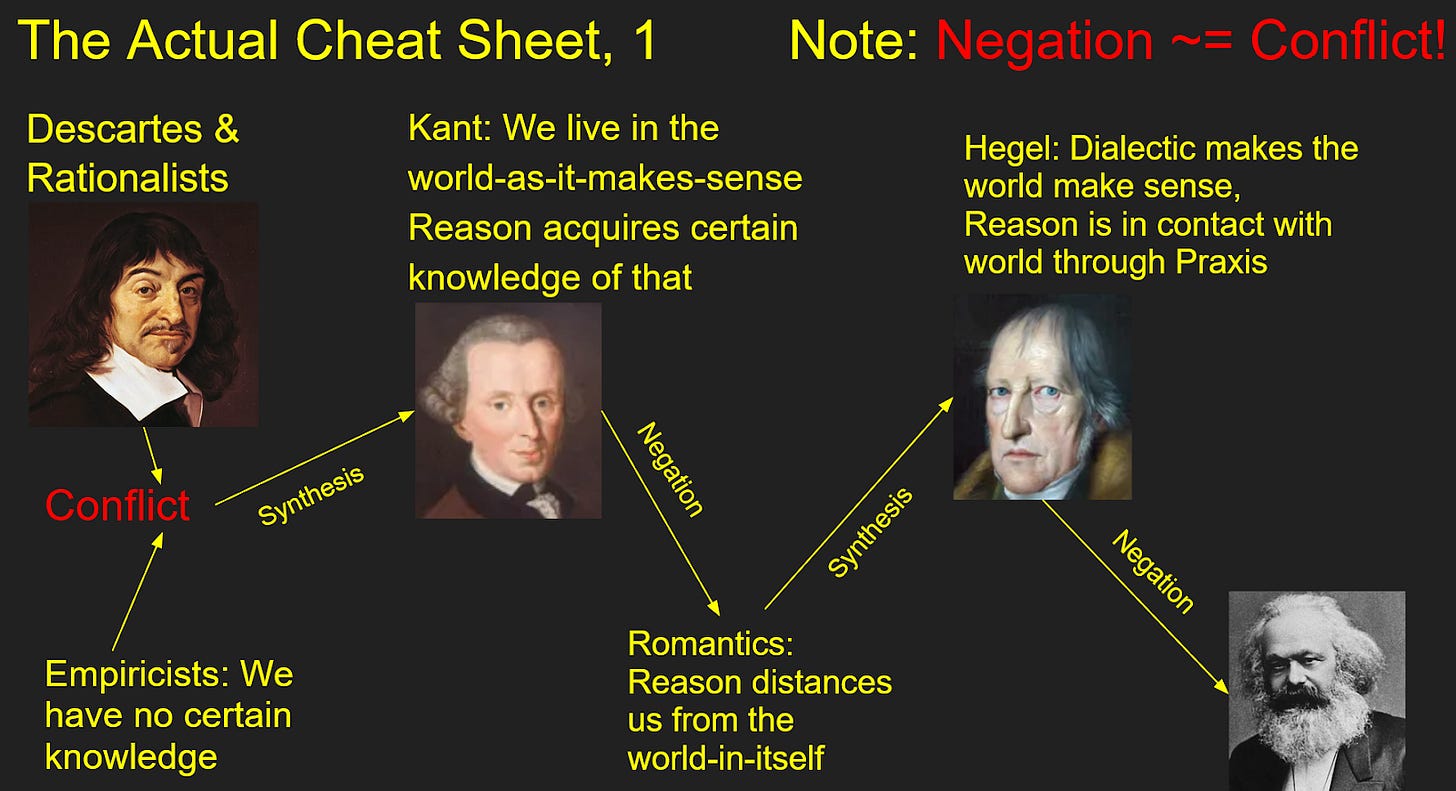

Descartes basically started a conflict between rationalists and empiricists with his radical doubt, calling reality as such into question.

Kant solved it by synthesizing the two positions into the world as it makes sense to us and the world in itself, and held that with no direct contact with the world in-itself, the former is what we care about. In the process he led the romantics to reject Reason to be in contact with the world.

By adding the dialectic to Kant’s list of fundamental components of the world as it makes sense, Hegel synthesized the romantic desire for contact with reality by conceptualizing us and our Reason as in a dialectical relationship with the world through what was later called Praxis.

Hegel’s descriptions of the dialectic at different levels of analysis sent waves throughout all of philosophy, and lead to endless thinkers trying to apply the dialectic, especially between Master and Slave, to their experiences in order to create objective knowledge.

Marx took Hegel’s ideas of history and created an antithesis to it, with a new emphasis on material reality. In this antithesis, the Master-Slave dialectic was seen between capitalists and workers, basically adapted wholesale to this concrete context.

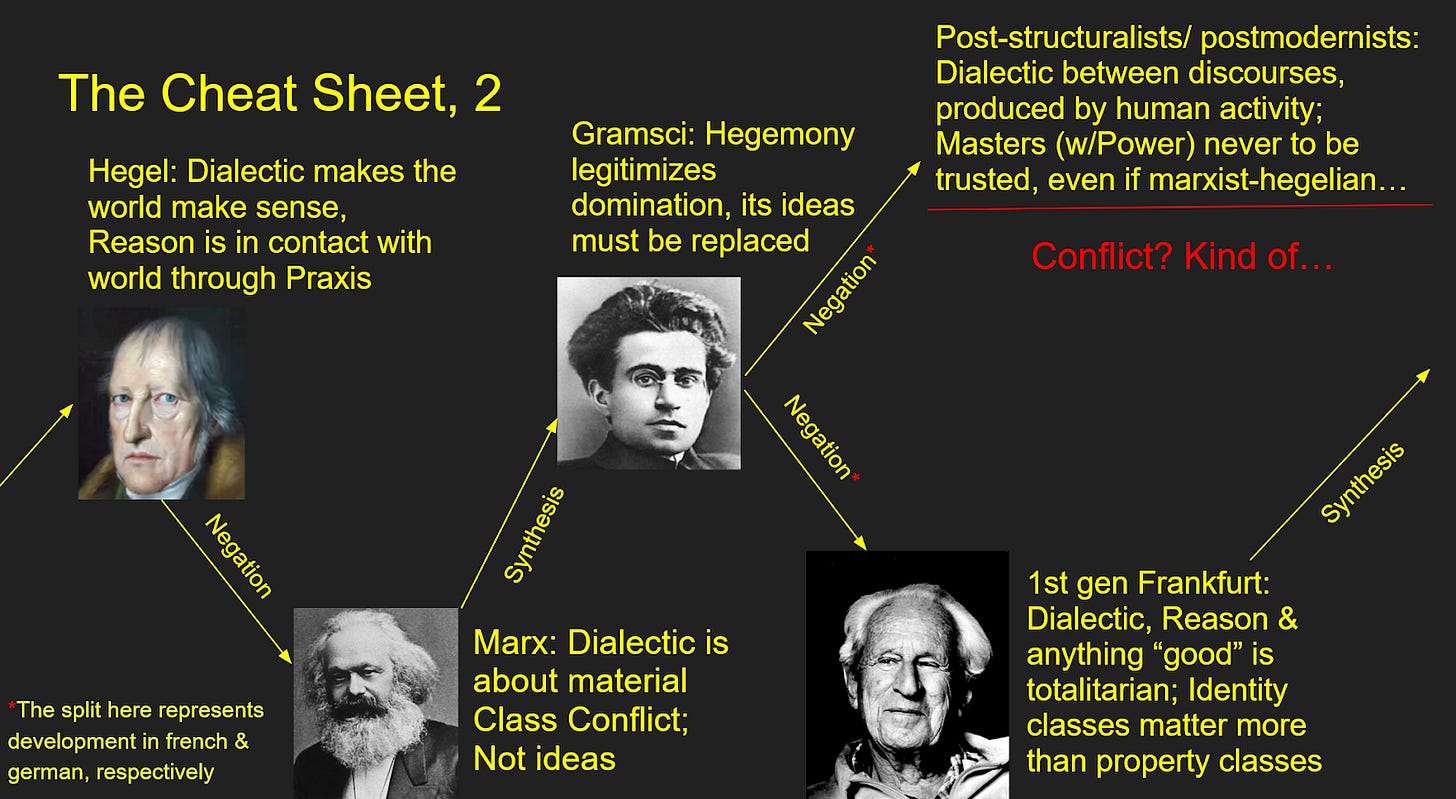

Marxists quickly realized that workers were not all on board with the project. With Gramsci at the forefront they explained this by saying that they had paid insufficient attention to the role of the cultural hegemony of the Master, and concluded that they had to create its antithesis from within the hegemony.

This interest in the hegemony and the workings of power led to structuralism with ideas derived from the dialectic, and ultimately to post-structuralism and an all-encompassing theory of the master-slave-dialectic between discourses that create the world more than humans do. This made them suspicious of all with power, even if they were marxist-hegelians.

Around the same time, the Frankfurt School lost faith in Reason and the dialectic of history, fearing its totalitarianism, not least in response to the Praxis of the Soviet Union. They turned away from saying that anything was good to avoid totalitarianism, but kept basically everything else.

They also concluded that Marx got the relationship between workers and capitalists under capitalism wrong, since it improved the lives of the workers over time. With Marcuse, they directed more attention to other master-slave-relationships for the dialectic, since those had more revolutionary energy, but maintained that there were deep problems with capitalism.

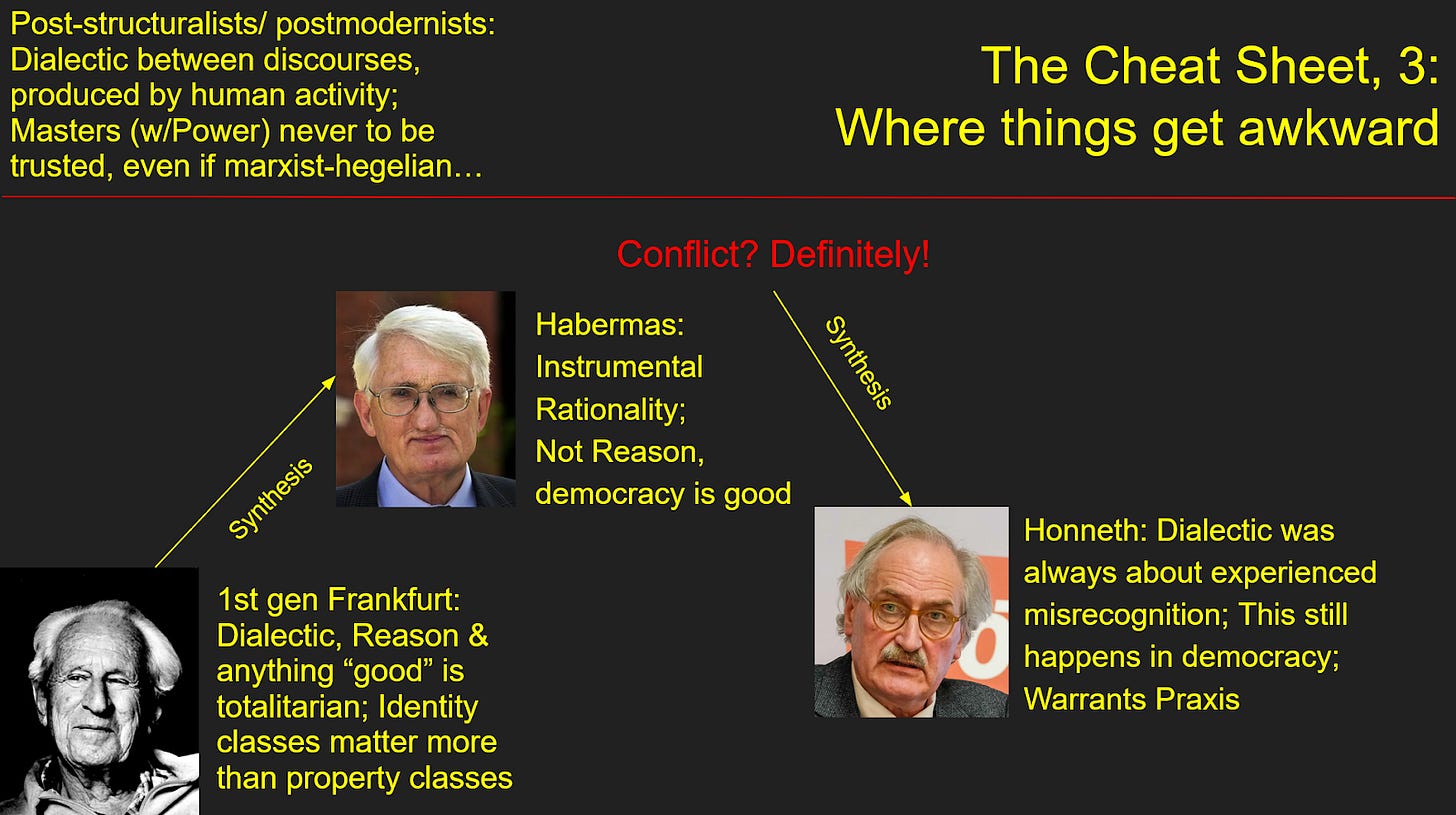

With Habermas, the rejection of Reason was reframed with a recognition of different kinds of rationality. The problems with ‘Reason’ were now limited to one kind of rationality, the instrumental Rationality of the sciences and the market, when it reached into the world of subjects. This allowed him to formulate an ideal state, which fits neatly as a goal for reform or a system for after the dialectic at the end of history, to produce the general will.

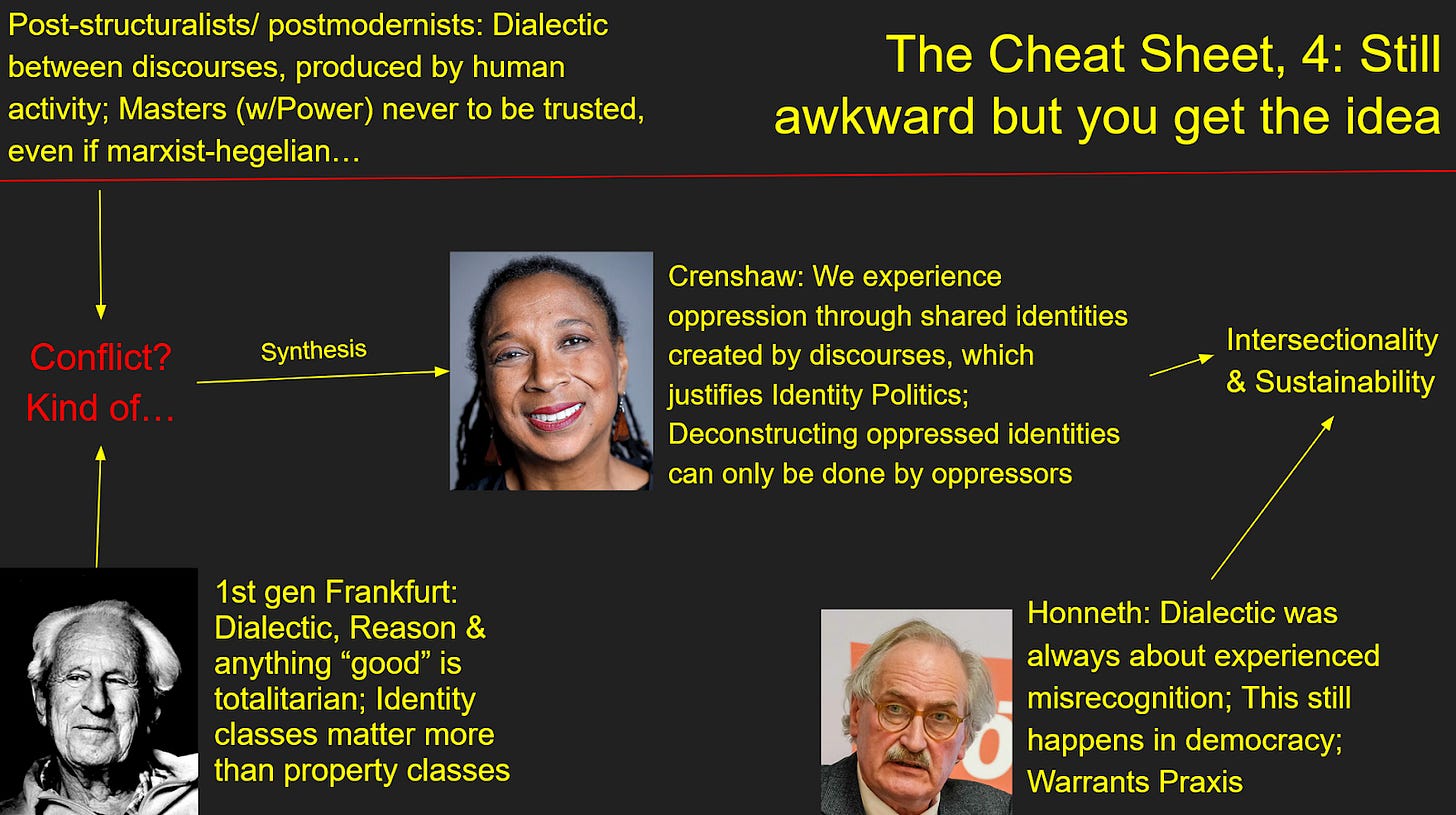

Honneth tried to synthesize Critical Theory with postmodern ideas like post-structuralism and discourse theory by looking at what might cause conflict in Habermas’ ideal state. He looked back to Hegel and reframed Critical Theory in terms of the experience of misrecognition, as a new totalizing theory to explain all conflict. This was the master-slave-dialectic with an emphasis on how the subjects must recognize each other as equals.

Crenshaw also synthesized postmodernism with Critical Theory to justify identity politics, a newer name for Praxis. She argued that the hegemonic discourses created identities by which it could oppress, and that being the target of this oppression created a lived experience of oppression which could unite people in identities as a subject.

Crenshaw also made a moral attack on those who would apply postmodernist methods to the oppressed people’s struggles for recognition, and responded to Marcuse’s call for a new sensibility with the conception of Intersectionality as that, seeing that unique oppression could exist in the overlap between any identities.

With this, the dialectic of today is about smaller and smaller slave-subjects within previous slave-subjects coming forward with all their criticisms. Since self-criticism protects the hegemony, it is discouraged, and no criticism from the Slave is invalid. Intersectionality became a sensibility for Identity Politics, which justified the Slave subjects coming together, but not the Masters. For Masters, the appeal came through Sustainability, and an infinite responsibility for the Other(s), to avoid and minimize conflict with the Slaves. For sustainability, the Masters instill the mentality of intersectionality in its Slaves, and do everything in their power to accommodate the Slaves at points of criticism. Any move away from this party line, for either side of the dialectic, constitutes an impulse from the right, and an expression of false consciousness, which protects the status quo of domination and leads us towards fascism.

This is the essence of left-wing philosophy, and this is the logic that will play itself out among people who operate in this paradigm. If you think I got something wrong I’ll be happy to hear you out in the comments, but keep in mind that I have been trying to keep this simple. Most of the people mentioned here have done a tremendous amount of work, developed unique terminology for what they describe and more. Indeed, this is why continental philosophy is so hard to understand; You have to be well-read to understand the double bottoms in what is said.

What I have neglected

Rousseau

I think this branch of philosophy can be said to have started at a couple of different points. The first is one I have neglected here, Rousseau. His philosophical speculations were a great influence on Hegel as well as the french revolution, but did not really fit neatly anywhere in the text. I have alluded to his notion of Democracy for the General Will, which I think constitute the philosophical background for democracy to socialism. In a thought-experiment, Rousseau suggested that people voluntarily came together to form states in order to get certain benefits, termed civil rights. What they had to give up to get civil rights was natural freedoms, as they put the General Will of the people above their own freedom in order to continue benefiting from the state. This stands in contrast to a liberal view of democracy, where the natural freedoms are natural rights, which the state should not touch, even for the General Will. Rousseau also had comments to make on things like the ownership of property, and I think he is worth a closer look, but I thought this was complicated enough without him, and at this point you probably agree.

Fascism

In making this, I considered talking about Fascism. It also grew out of Hegel’s ideas, and even applied Marx’s ideas, only in a different manner. However, calling it “left-wing philosophy” would get a lot of people mad, just as calling it “right-wing philosophy” would. Nobody who is not himself a fascist wants to take ownership of fascism, and for good reason; It is patently brutal, and openly discourages independent thought. There were other reasons too, however. First of all, there is a lot less of it, if we don’t count the philosophy that I have covered here. Second, since there are a lot more people who want to take ownership of, say, marxism, it is a lot easier to become familiar with left-wing philosophy second-hand. Third, I watched youtuber Ryan Chapman’s videos on fascism and I think he does the topic justice. I highly recommend checking those out if you haven’t already.

Cheat Sheet for Right-Wing philosophy?

Another question I have pondered is if it is possible to make a cheat sheet for right-wing philosophy in a similar manner as I have done for left-wing philosophy. I really don’t think it is. This is because what is right-wing is usually defined by the questions forwarded by the left, in a dialectical pattern, if you will. A consequence of this is that, while there might be a coherent logic to left-wing philosophy, the particularities of a given country, with its unique culture and resources, means that what would be responding to left-wing philosophy should be diverse. Calling it incoherent would be unfair, since I’d be looking at a different set of arguments that might align with left-wing philosophy on some counts but not on others in every instance. Expecting people who disagree among each other to cohere just because they all disagree with something in a massive philosophical stream would be a tremendous mistake. Not least because it is possible to have reasonable disagreements about a lot of what I have covered here.

As an example: Is it really a given that only privileged people have the excess energy to deconstruct identities? At the same time as deconstructing privileged identities and discourses is a legitimate form of praxis for the oppressed to engage in? It is not strange for people to dispute Crenshaw’s synthesis of critical theory and postmodernism. It is far from the only thing people can object to reasonably.

Politics

This series was always about left-wing philosophy. It was never envisioned as a guide to left-wing politics, so while there is a lot that could be said about distinctions between, say, communism, socialism, different kinds of communism and socialism and social democracy, as well as their respective historical developments, it is philosophy that interests me, and which I set out to explain. You will have noticed by now that this series has been very light on details about political systems. However, politics often follows from philosophy, and you can learn a lot about politics from philosophy. For example, communism can be summarized in a single phrase: Abolition of private property. In the philosophical context, that means abolishing the social construction that makes inequality between masters and slaves possible. With that, its transferability to various kinds of privilege - among other things - should already be clear, but I want to note that abolition is one of the words that refer to dialectical synthesis. Abolition destroys the conception of private property that exists, and changes the frame so that something like private property exists which does not create inequality. Therefore it both subsumes and elevates, and is usually translated from the german “aufheben” or “aufgehoben” to sublation, which combines subsumption and elevation into one word. Abolition is, as noted, another translation, with emphasis on what is done away with.

Where is Jung?

When I covered Jung’s ideas and how they resemble the dialectic, that is not least because combining the two seems like an obvious connection to make. But what happens when we take Jung’s ideas of self-development and apply them to Willig’s 2012 program for Critical Theory? For now, I leave this one to you. I will only say that it is a wonder to me that left-wing philosophers have been so fond of Freud but I have never seen them discuss Jung. Unless we count the feminist Camille Paglia, who praises his student Erich Neumann and argues that left-wing philosophers have vastly overestimated the role of language.

Trygve Taranger is an autodidact software developer, data scientist and musical composer with a Master’s degree in Media Practices. While in university, he accidentally found himself learning about Critical Theory every single year in most of his courses. Trygve is most active on X as @CuriousnTT, where he explores different ways to think about things.