A Cheat Sheet for Left-Wing Philosophy

Part 3

(Editor Note: This post is a script from a video series and will be published as an E-Book in the near future. This is only part one. The video is provided but the text and diagrams are below.)

The Structures of Dialectic

When explaining Postmodernism, it is normal to start with breaking down the word. The “post” is the same as in “posteriori” from part 1, roughly meaning “after”. “Modernism” is a name given to a common sentiment near the start of the 20th century, a sense that the world was making progress, and that tradition would be left behind. You can compare this to the Dialectic of Historicism I explained earlier in this series. Postmodernism is what comes “after” this sentiment has died, particularly among left-wing philosophers, and is a lot like what we saw with Adorno in part 2. However, it can die in other ways as well. For example, it could simply mean no longer taking Marx’s prediction that a communist Utopia was inevitable seriously. Postmodernism is often said to reject modernism, but at the same time, the people who are considered postmodernists, Michel Foucault and Jacques Derrida chief among them, often reject the label. Moreover, postmodernist and post-structuralist are labels used interchangeably, and postmodernists are also often called structuralists or post-structuralists, even though post-structuralism also rejects structuralism. So what is going on here?

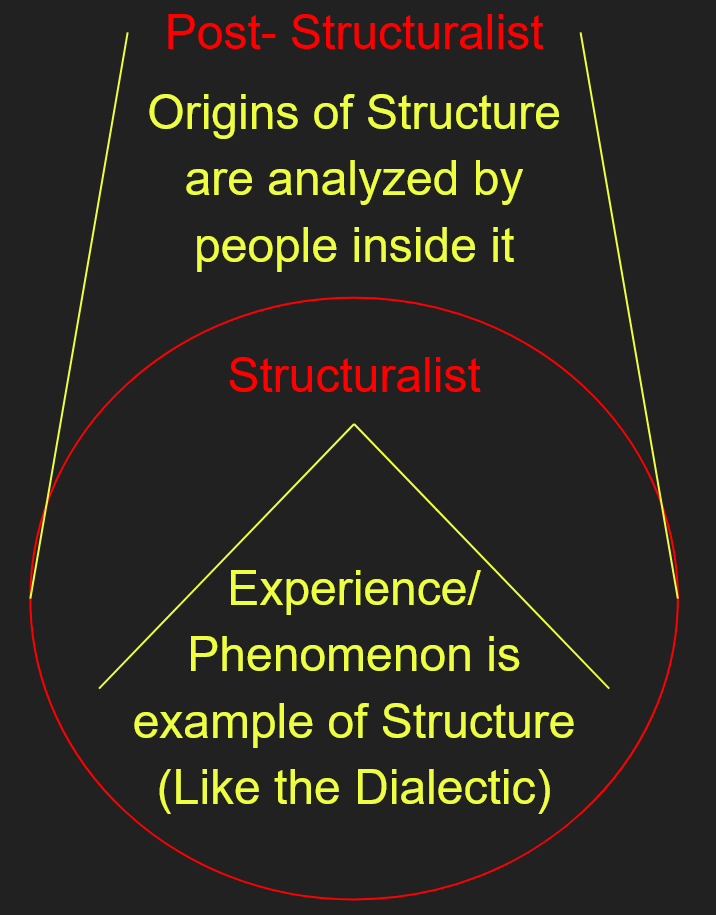

Let us start with structuralism. Structuralism sees the world in terms of structures. A structuralist analysis connects a phenomenon, or to echo Kant’s analysis of objective knowledge, a subjective experience, to a larger structure. In this way, it tries to say something meaningful about the phenomenon as an example. This can take many forms with many different kinds of structures and phenomena, and can be done both with the dialectic itself and with the products of a dialectic, like the social structures of the Master’s Hegemony. When Derrida applied the master-slave dialectic to word-pairs and concluded that word-pairs depended on each other, the structure of their relationship, for their meaning, that was a structuralist analysis. To get a bit meta, this series of videos is a structuralist analysis insofar as I have tried to connect all I know of left-wing philosophy to Hegel’s Dialectic.

Post-structuralism essentially does the same thing as structuralism, but notes that the human analyst is part of these structures, and therefore regards all analysis as biased and unreliable. Therefore, the main difference is that post-structuralism supplements structuralism with a study of the greater system and how it came about, because it sees these as the source of the bias. When Foucault did “archaeology”, this is what he was doing. It seems like there is no fine line distinguishing post-structuralism from structuralism. In my opinion, even calling it a rejection of structuralism is pushing it.

Hegemony taken to the limit

Interest in studying the development of a cultural system was not new with post-structuralism. As noted in part 2, marxists showed increasing interest in the hegemonic structure they saw as designed to make the necessary social changes seem impossible from around 1900. It is also worth noting that a lot of the postmodernists were part of the same circle, along with marxists and, to use the formulation currently on Foucault’s Wikipedia page, “ultra-left activists”, and that Foucault and Derrida were no exception to the rule that these were deeply influenced by Marxism. Foucault also wrote his Master thesis on Hegel. It should therefore be unsurprising if a lot of the ideas are very similar to what we have discussed earlier.

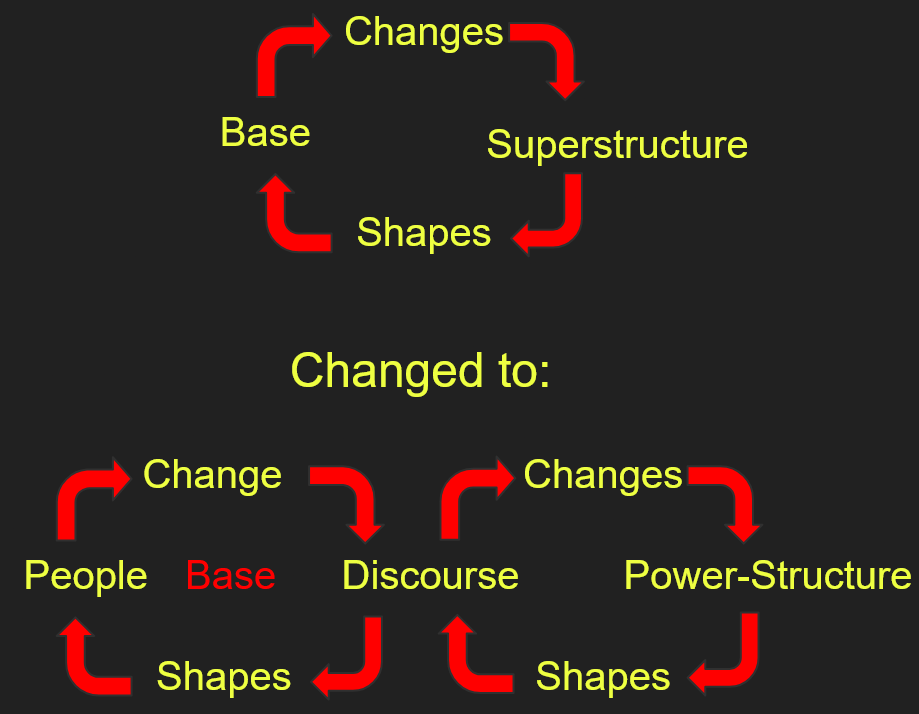

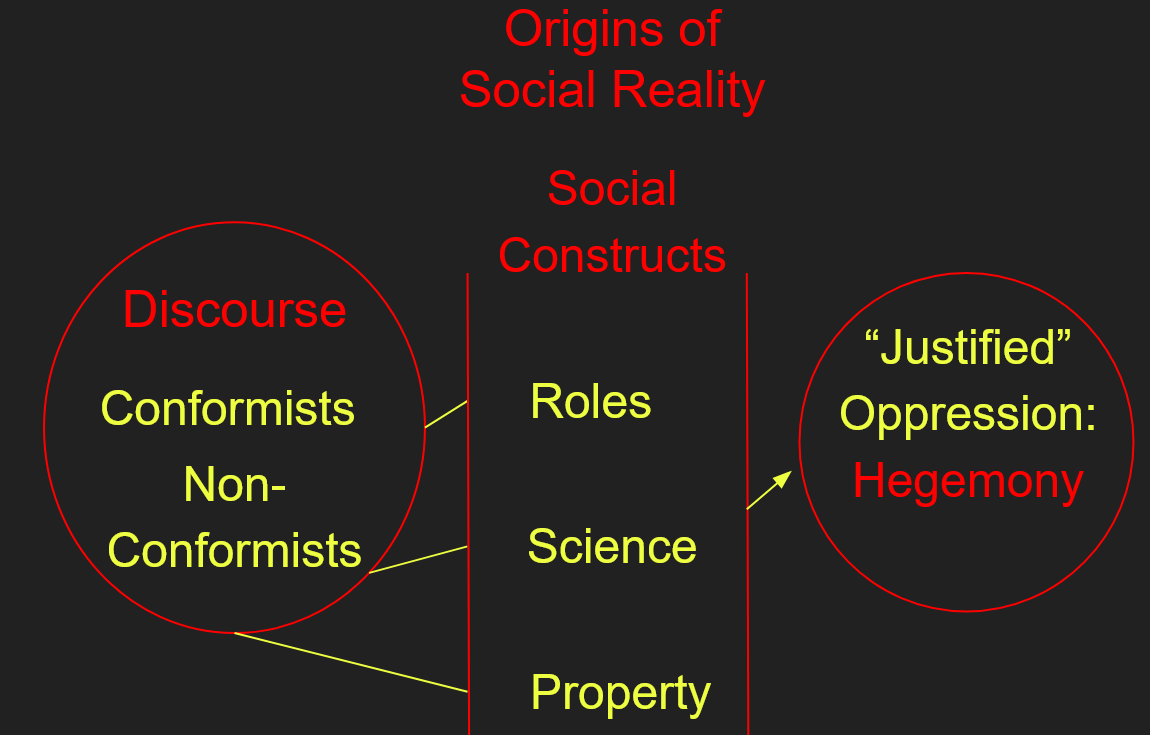

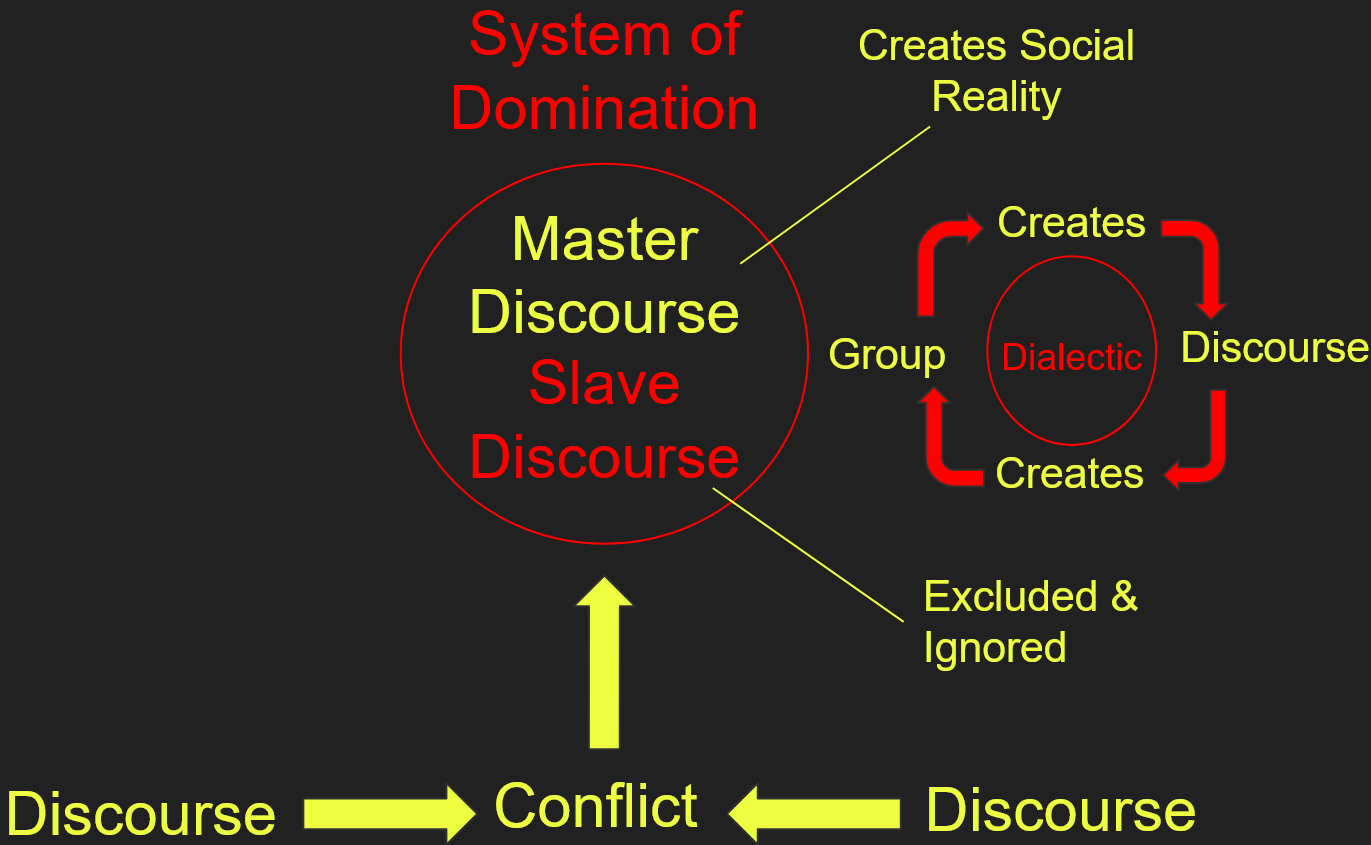

Putting it simply, in the analysis of post-structural postmodernists, the hegemony moved from the marxist model of a superstructure which justifies who has power to a power-structure that perpetuates itself. Marxists saw the superstructure in a dialectical relationship to what they called the base, which determined the form of the superstructure, and which together formed what they called the political economy. Postmodernists and marxists of the later 20th century adapted this model to new contexts, discussing things like the political economy of race, knowledge, sexuality, and so on. To Marxists, the base was usually conceived as available resources and the tools available to make use of them. To later iterations of marxian theory, the material resources were increasingly a side-issue, as culture and the means of cultural reproduction, like speech and action, took center-stage. Postmodernists often referred to these as discourses. The things discourses create are generally called social constructs.

Discourses were seen as necessarily contained within a power-structure, which limited what might be said and why. This structure was not physical, but distributed in the minds and expectations of the people living within the world it defines. In the discourse of science, you would have scientists, and people who did not show sufficient understanding of the scientific discourse, who did not say the right things in the right ways, would be excluded and derided in various ways, thereby preventing them from being a part of the discourse, and perpetuating it in its current form.

The power-structure and its discourses is Gramsci’s Hegemony by another name, but it applies to everything. It opened up an infinite number of angles for analysis through the master-slave-dialectic. By seeing the discourses as controlling who decides what is correct, what may be said about social formations, vast numbers of people can now be seen as excluded from discourses they did not understand and therefore also excluded from deciding what may be said, what power-structures can be produced. These in turn control the production of social reality, the world we share, by limiting what can be socially constructed.

Truth and Knowledge, Decided by Power

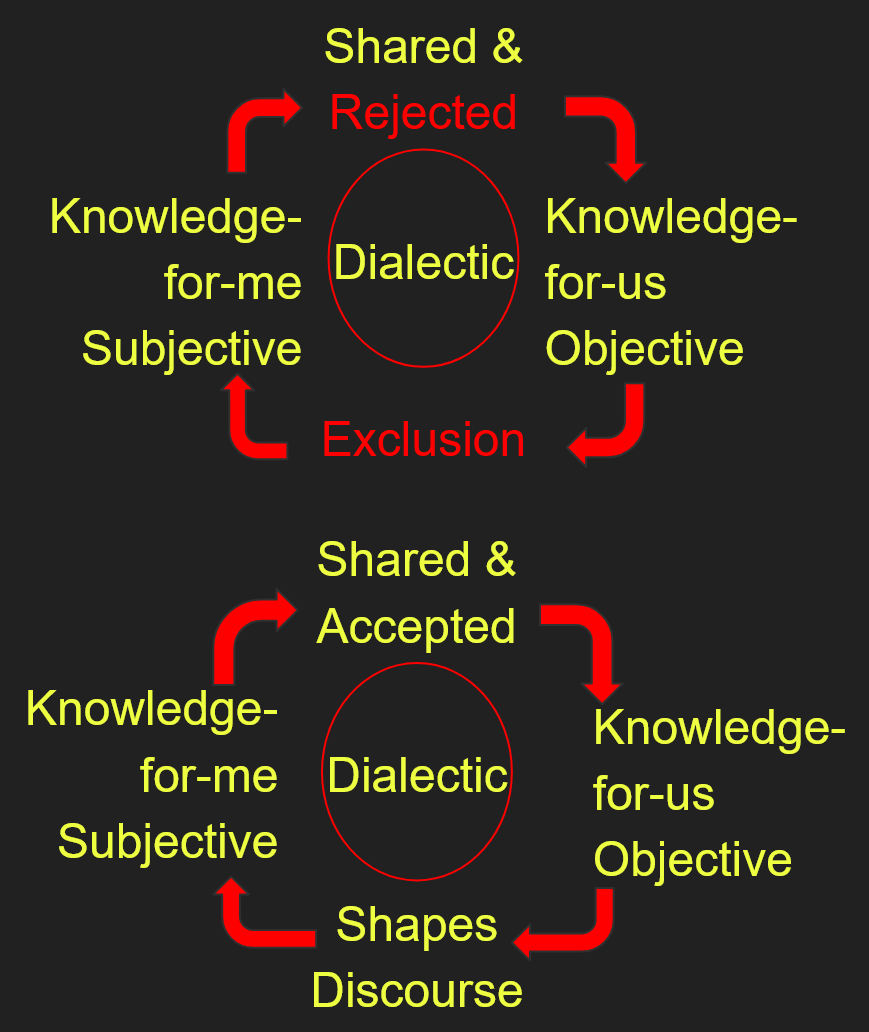

In discussion of discourses, one should know that truth and knowledge hold no special position. What constitutes truth is also determined by the power-structure, which will punish the production of statements that don’t fit with the broader discourse. And the same goes for knowledge. Referring back to Kant’s idea of objective knowledge as the world as it makes sense to us, and how objective knowledge is created by connecting experience to assumptions we cannot help but to make, and Hegel’s addition of the dialectic to those assumptions, how discourses work becomes another such assumption, developed in reference to the dialectic. As you can see, with discourses it is no exaggeration that postmodernism applies the dialectic to everything.

The Horrors of Exclusion

For those who are excluded from a discourse, the opportunity to produce objective knowledge is limited or even denied. In this way they are prevented from contributing to the creation of objective knowledge, and their truths and their knowledge is lost. This is a matter of definition: What the excluded think is truth or knowledge is not factored into the discourse, because this is what exclusion means. Consequently, the meaning of words is decided by those with the most power and influence over the relevant discourse, and perpetuated by basically everyone because the alternative is punishment, much like in the sociological model of the spiral of silence, and this produces culture. Exclusion from this process constitutes a form of erasure from social reality, and can go to the point where the excluded might as well not exist. Thankfully, exclusion is rarely absolute.

Competing Discourses, Competing Cultures

As per the theory, a discourse can be dominant. It can subjugate and exclude another discourse when it comes to a topic. One dominant discourse is what Derrida called “phallogocentrism”. With this word, Derrida connected the idea of the phallus, or the penis, or masculinity as such, with the idea of logos. He effectively said that these are the same thing, and that it is the dominant discourse in the western world. What is excluded, then, is whatever isn’t phallogocentric.

This is easier to understand with reference to rhetoric, the art of convincing others. The three basic ways someone can accomplish this is through an appeal to authority, called ethos, emotion, called pathos, or logos. As it is, logos is a very complicated term with many meanings, but in rhetoric, it commonly refers to argumentation through reference to data, logic or both. If someone is logocentric in a rhetorical sense, he dismisses arguments that appeal to authority or emotion, and asks for data or logic in support of the argument, and preferably both. In this way, the discourse of at least logocentrism dominates and excludes other discourses that could talk about the same topics.

For Derrida, there was a connection between phallus and logos, which suggests a connection to the feminist conception of the power-structure, the patriarchy. Making the connection that a discourse serves the hegemony of a group that is, generally, closer to power seems like a natural extension of the logic, and this kind of suspicion of discourses which co-exist with an established system of domination is very typical for the tradition. Some take the discourses to be set up in ways that serve the oppressors for intrinsic reasons, while others think the discourses have no intrinsic connection to the oppressors and that excluded groups would do well to embrace some dominant discourses because the exclusion stemmed from some other discourse.

The discourses generally come from groups of people who co-existed in one culture. As noted, post-structural analyses emphasize the significance of their historical developments. These developments are largely separate for various cultures. Yet a discourse from one culture might have come to dominate people in another, in a clear parallel to the master-slave-dialectic. Therefore, in order to give the people of the subjugated cultures a fair chance at contributing, it is seen as necessary for the two cultures to recognize that they and their discourses are, in fact, equal, so the exclusion can stop and both subjects can be equal contributors to the dialectic. Thus, post-structural analysis led postmodernists to a form of cultural relativism. Many showed little interest in the integration of the different cultures, which they would rather see live peacefully side by side than becoming one.

As you can see, the logic was already there in the master-slave-dialectic. All you need to change is replace the subject, to move from individuals or groups of people in the original dialectic, to discourses. And the discourses create social reality. It is not far-fetched to compare the sum of discourses to God, if one is more concerned with social reality than the rest of reality, which left-wing philosophy generally is.

Postmodern Praxis

A prime example of this is Praxis, which I previously noted had two meanings. A descriptive meaning, as something you do for as long as you live because there is nothing you can do that isn’t Praxis. And a prescriptive meaning, as something you should do to be more than an animal, which solves contradictions in your world and lets you get into contact with reality by trying to change social life. Praxis still exists in postmodernism, but it has taken on a new form, to reflect a loss of faith in the historical dialectic, but as well as a persistent desire for liberation from dominant discourses of the power-structure.

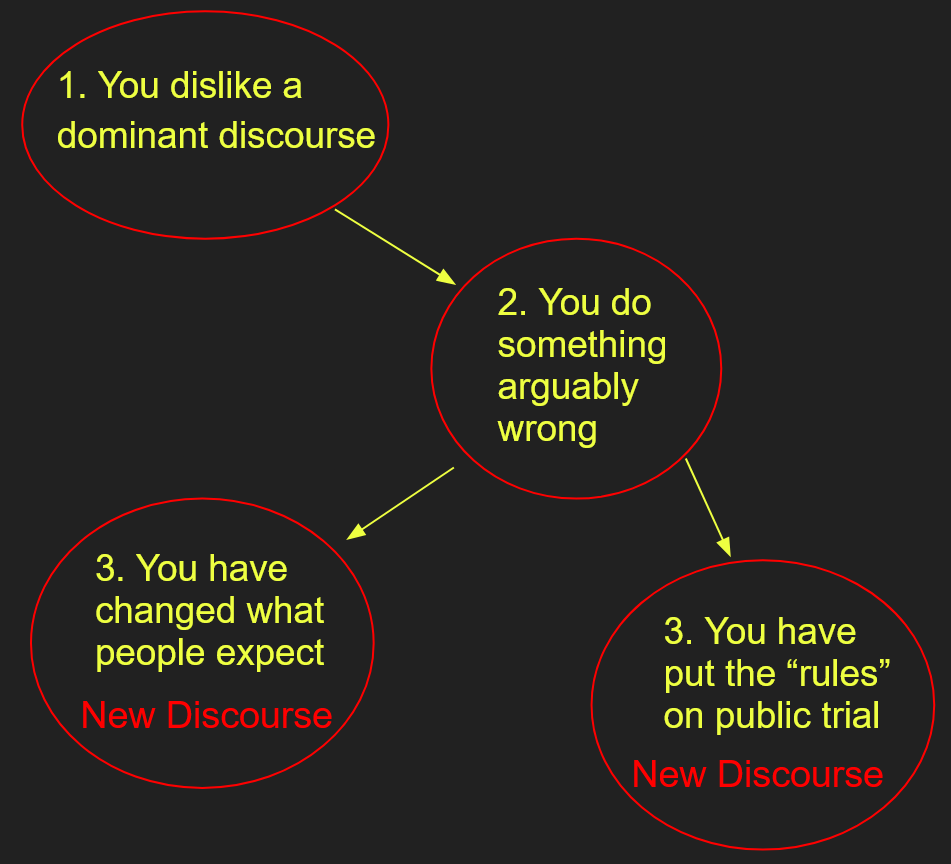

Postmodern Praxis is sometimes simply explained as play. Instead of following the rules of the surrounding discourses, the postmodernist tries to do things simply to see if it can be done, to test the powers in play. This might take the form of experimenting with non-conventional sexual activities. It might take the form of doing something that is normal in one setting in another situation. It is basically a form of resistance against doing what the postmodernist perceives that he is being told or encouraged to do, demonstrated by trying to do something that he perceives that the system is discouraging him from doing. Thus, it is often on the edges of what you might find acceptable, and sometimes it might pass beyond the pale. For postmodern praxis, the purpose of this activity is to challenge and resist dominant discourses, to break down the rules that limit them, and allow for people to be and do whatever they want.

By speaking and acting in ways that don’t fit with the dominant discourses, postmodernists engage in the activity that creates discourses, and contribute to a transformation of social life by changing the rules. People who see or hear them might come to think the rules are arbitrary, that it looks fun, or something else to the same effect, and support the transformation as a result. Therefore, postmodern play is regarded as deconstructive to dominant discourses and their rules.

Derrida made a lot out of deconstruction in his work, which had a particular focus on language. All the same, he never really explained deconstruction or what it was, beyond the function of undermining structures. The parallel to postmodern play more generally leads me to think it is essentially the same: Postmodern Praxis.

Because of their characteristic skepticism of grand narratives, such as the dialectic of history which creates God, you can expect postmodernists to engage in this regardless of the discourses in question. However, there is no reason to expect the same postmodernists to engage in praxis in the same ways across discourses. Postmodernists also have their biases, and want things. They will probably be more active in Praxis when the discourses in play enforce rules that prevent them from doing what they want. In this respect, postmodern play becomes an additional means for the oppressed to change social reality, in addition to the problematizing methods of negative dialectics. The approaches can be complementary, as they are not mutually exclusive. It is merely the difference between doing things that are considered somehow wrong by dominant discourses, and saying that there is something wrong with the dominant discourses.

Harmful Stereotypes & Bias

Harmful Stereotypes has become a common phrase since the coming of postmodern theory. Here is how it makes sense from the postmodern angle. Everything we do can either change the discourse, or let it stay as it is. Actions and statements that reference something stereotypical of a group perpetuate stereotypes about that group in the discourse. Just like how we saw when I explained reflexive truth in part 2, stereotypes we apply to people can also become true - at least to some extent. When these also imply that there is something to the people the stereotype is applied to which is considered bad in the broader discourse, the stereotypes are thought to both justify and cause exclusion for those they’ve been applied to less consideration. This is harmful, bad, because exclusion approaches erasure as we move towards its limit, and is a form of oppression. Condemning another culture or in some other way chauvinistically promoting your own is bad by the same count. Such actions are also taken to indicate biases, which contribute to a pattern of similar activities that perpetuate oppression in the discourses.

Difficulties with Postmodernism

For the broader picture of left-wing philosophy, postmodernism posed a problem. Its analyses would apply equally to anything they constructed through Praxis as it did to everything else. Therefore, acknowledging it made it very difficult for other philosophers to avoid accusations of hypocrisy. All the same, as we saw with Honneth, there was a desire to incorporate it into the broader theory; Honneth wasn’t the only one who sought a synthesis, and by his time, his Frankfurt School might not even have been the most influential in the world of Critical Theory. Still, let’s have a look at the postmodernism in Honneth’s Critical Theory, and what it cost.

Honneth considered discourses and exclusion from them, but ultimately rejected it in favor of damages to the individuality of subjects. You may recall that he still acknowledged exclusion, and you may note that the individuality of subjects does not automatically mean individual humans in this tradition, but can refer to groups as well. Honneth tried to make his theory so general that it applied to all life, not just humans, and we can speculate that it was because of how postmodernism put everything on the same level, but I can’t say that for sure with what I have read. Since postmodernism is suspicious of and corrosive to any and all standards, standards for misrecognition could not hold, but still contain an ethical imperative: No one can be excluded from the knowledge-producing processes without it constituting misrecognition on the second layer, that of Rights.

Intersectionality

The most visible synthesis of postmodern theory and more traditional critical theory came from a founding Critical Race Theorist, Kimberlé Crenshaw. Since Critical Race Theory has received a lot of attention recently, and largely mirrors ideas I have already covered, only, with race in the center of the analysis, I won’t get into it here, beyond noting that through Angela Davis, who was a major influence on many of its founders, there is a direct line to Marcuse. No doubt there are other connections, including to later figures in the Frankfurt School, but if they exist they are less known. Given some of the things Crenshaw says it seems likely that she was familiar with Marcuse’s work.

Crenshaw’s synthesis is known as intersectionality, from around the turn of 1990. On the face of it, there is no apparent fusion of Critical Theory and Postmodernism here, as you will see shortly. However, Crenshaw was explicit in it being one. It is therefore plausible that the basic explanation of intersectionality has a double bottom, which should be more understandable with what we have covered.

The basic observation of intersectionality is that it is possible to be oppressed on the basis of combined identities as well as single ones, that attempts to solve oppression which only try to help women or only try to help black people might allow for black women to be left out. It allows for the support directed to women to go to white women exclusively, and the support directed to black people to go to black men exclusively. If you imagine it as an intersection for cars, black women could then be hit by trucks from both directions. If you imagine it as a venn-diagram, the people in the intersecting parts of the diagram can be left out of attempts to offer support. Therefore, the overlap between all identities should be considered in their own right as distinct identities.

The Intersectional Dialectic

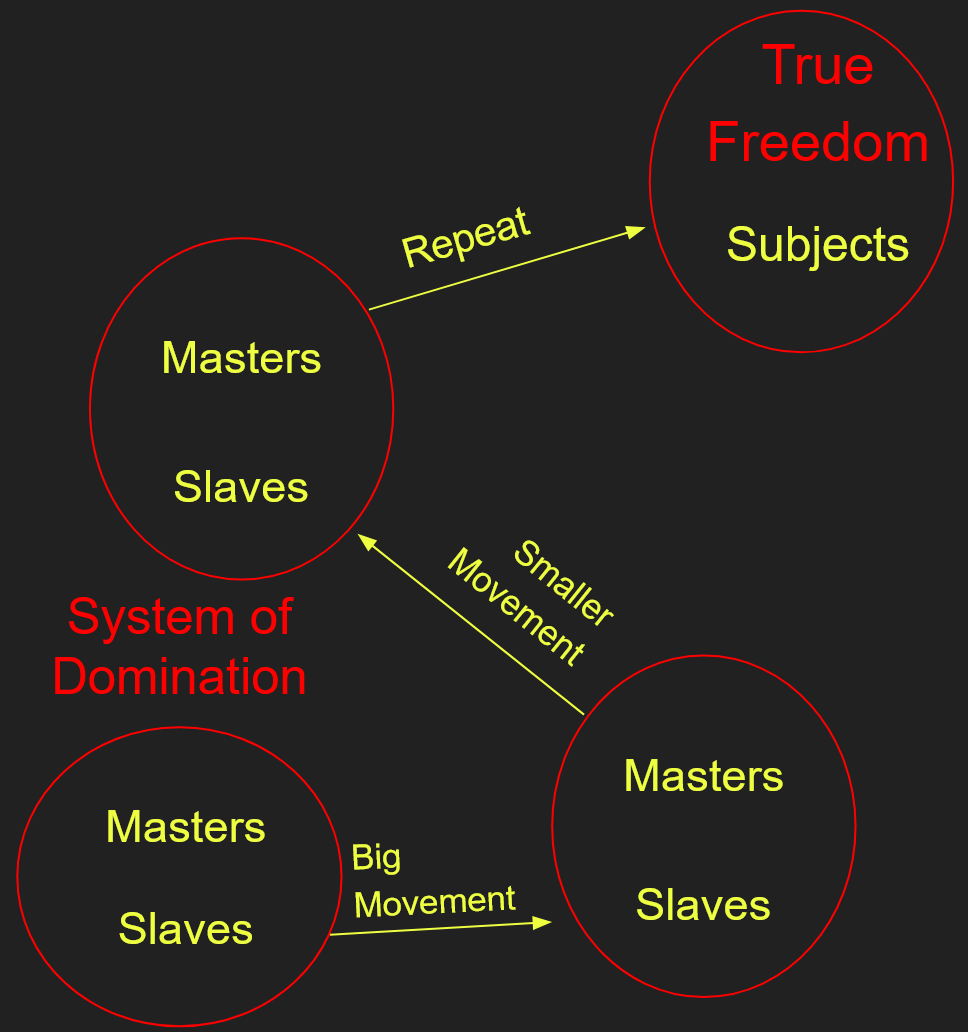

There is a lot more to intersectionality that is worth noting. Building on previous theory and calls for solidarity, it formed a unifying framework for traditional marxists, feminists, critical race theorists, and many other branches of critical theories. It said that the feminist movement oppressed Black feminists, and that the Black Panther-movement and other advocates for racial justice oppressed black women. It said that these movements should strive to fix themselves as well as the broader society. Paraphrasing another founding member of Critical Race Theory: The bigger movements would step forward with their claims to proper recognition, then, as they made progress, smaller groups within them would step forward with their claims, then smaller groups again, and so the dialectic progresses. In other words, we have essentially returned to the dialectic of history.

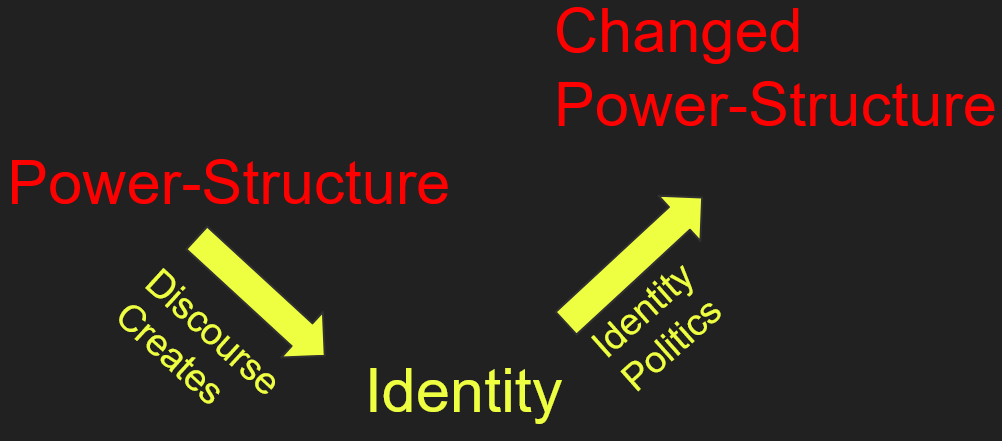

With intersectionality, everything I have brought up so far is melded into one soup. Even postmodernism, which raises serious questions for the other components of modern left-wing philosophy, was integrated. This was accomplished by seeing the power-structure, which some called the matrix of domination, as creating the identities it oppresses, by inventing and then perpetuating discourses that exclude and otherwise oppress based on something arbitrary. The oppression is now seen as happening for the same reason for all those who have the same identity, thereby creating a shared experience of oppression, a shared subjectivity. This subjectivity is the subjectivity of a Slave subject in the dialectic, and the shared experience legitimizes what by now was called identity-politics: Coming together around a shared identity to demand or implement changes in social reality. To use terms we have discussed previously this is simply Praxis at a large scale, if you prefer.

To defend against the postmodern impulse to deconstruct even these identities,Crenshaw effectively countered as follows: Those who are really oppressed don’t have the luxury to deconstruct the identities that oppress them. Formulated the other way around, if you can deconstruct these identities that is because of your privilege. Since you have privilege, you are part of the Master-subject in the exchange, and since you use your privileges to perpetuate and defend the oppression of the Other, you are basically a bad person. You are not engaged in Praxis as a good Master, a good ally. This moral condemnation had enough power to justify postmodern methods in the service of identity politics. We may also note that, if we follow Kant’s notion of objective knowledge and we accept the dialectic as synthetic a priori, as an assumption we can’t help but to make, this moral condemnation is objective knowledge.

The New Sensibility

Crenshaw forwarded intersectionality as a new sensibility, likely with reference to Marcuse’s speculation that it would be required. Since intersectionality encapsulates master-slave-relationships in all their forms, it is well suited to the job, to making people resist domination, a characteristic of these relationships, in all its forms. Which was what Marcuse thought the new sensibility would have to do.

By 2012, and to the great frustration of people who still subscribed to earlier versions of critical theories, this sensibility had come to dominate Critical Theory, even in places where its name was not yet known. It faced competition, as others attempted to do the same under names like “sustainability”, and one could argue that “solidarity” itself constituted an attempt at the new sensibility. But one would be a fool to think these were incompatible. Solidarity is already incorporated in intersectionality, between the various Slave subjects whose members stand together in allyship even when they are the Masters in the relevant conflict.

Sustainability with Stratified Conflicts

Sustainability is trickier, but makes sense once we are clear on something I have not called attention to yet, called conflict theories, specifically stratified conflict theories. These hold that societies contain different groups who want resources, which in later theories is replaced by power, for themselves. When stratified, they also hold that the groups are distinct classes, even if some people move between them. You need such groups for a master-slave dialectic between groups, as these are the conditions under which one group can be better off than another. However, since the groups want resources for themselves, this invites conflict from groups that are worse off.

Since conflict is unpredictable and chaotic, and there is no telling what scale it can grow to, conflict, and by extension social stratification, or social inequality as it is also known, is undesirable because it is unsustainable. Which it is, because conflict beyond a certain scale can put all of society at risk. It also incorporates solidarity, and is often humble to the point of listening to all complaints, all criticisms.

Sustainability and Intersectionality, Master and Slave

Insofar as there is a difference between these two attempts at a new sensibility, it is the difference between sustainability desiring reform to preserve good things in society, and intersectionality desiring revolution to remove bad things from society. We can understand Honnethian Critical Theory to lean towards sustainability, since it wants a state to protect people from misrecognition. The notions of privilege and false consciousness, for their part, pull more towards revolution, and are more central in the intersectional logic.

Since those who seek sustainability engage in the Praxis of the Master-subject by listening to and accommodating those who engage in identity-politics, it seems plausible that the intersectional logic will be taken to its ultimate conclusion, unless the sustainability-camp of left-wing philosophy eventually decides that the intersectionalists are going too far. At that point, there would have to be enough people in the sustainability-camp saying no in unison, or the ones that still engage in the Praxis of the Master will accommodate intersectionalists by getting the dissenters out of the way. Recalling Marcuse’s thoughts on tolerance, the dissent would be an impulse from the right, and be understood as leading towards fascism rather than liberation because it says something is good. In any case, it should be clear that there is no hard line separating sustainability and intersectionality as distinct attempts at creating a new sensibility; It is mainly the difference between the sensibility in the Master and the sensibility in the Slave, with the same end-goal in mind; The perfect world.

Trygve Taranger is an autodidact software developer, data scientist and musical composer with a Master’s degree in Media Practices. While in university, he accidentally found himself learning about Critical Theory every single year in most of his courses. Trygve is most active on X as @CuriousnTT, where he explores different ways to think about things.