A Cheat Sheet for Left-Wing Philosophy

Part 2

(Editor Note: This post is a script from a video series and will be published as an E-Book in the near future. This is only part one. The video is provided but the text and diagrams are below.)

Where there are Masters and Slaves…

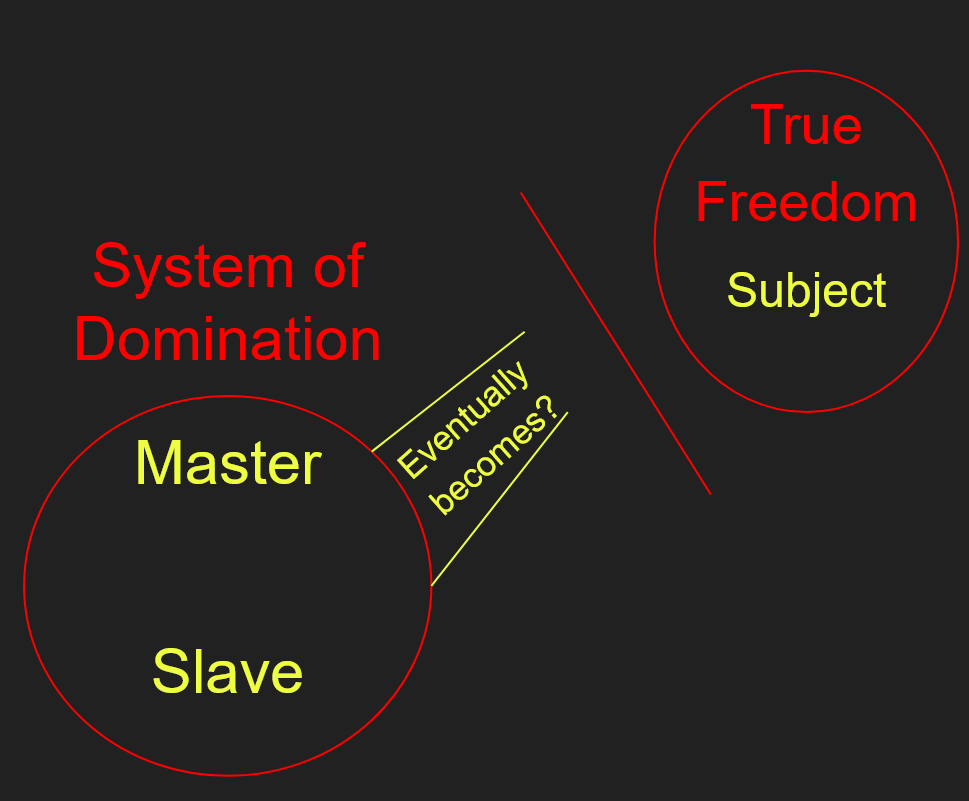

As noted in part 1, if you accept both the Kantian description of what constitutes objective knowledge and that the reality of the dialectic is a fundamental part of how the world makes sense to us, then relating personal experiences to the dialectic produces objective knowledge. This has been a popular practice among left-wing philosophers, regardless of whether they accept both these premises.The Master-slave dialectic is particularly popular.

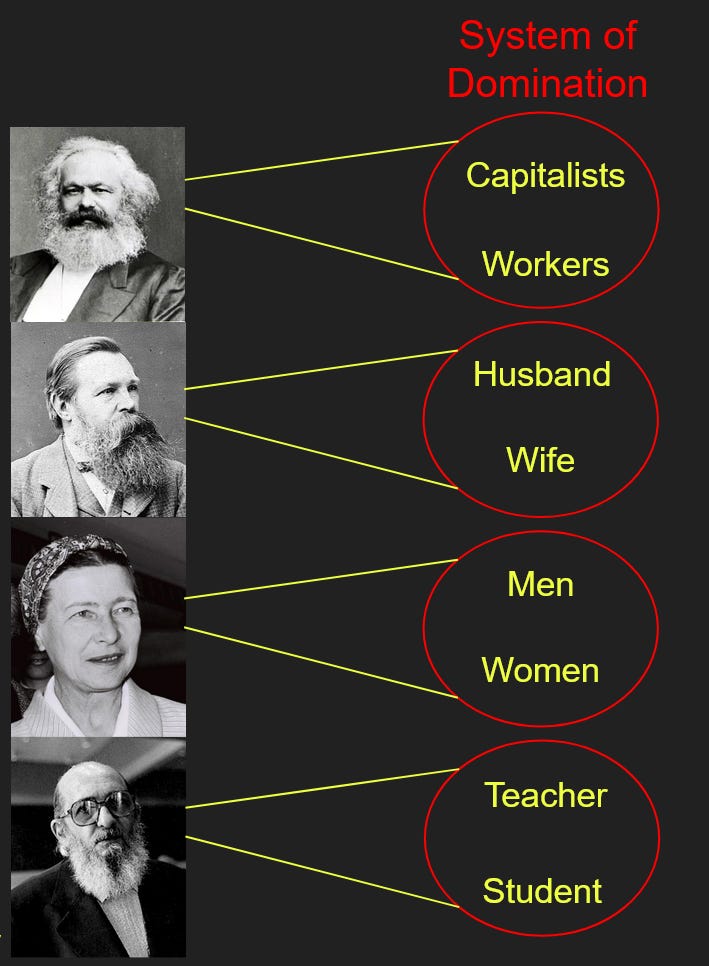

Marx saw the master and slave relationship between capitalists and workers. Engels later wrote about it between men and women in the family. Simone de Beauvoir, Sartre’s partner, did the same at a much greater scale. Paulo Freire saw it between teacher and student, as part of the greater system which excludes those who don’t fit in. Derrida, as noted previously, made what amounts to a near-exact replica of the master-slave-dialectic in his analysis of word-pairs; These are but a fraction of the ways left-wing philosophers have found the dialectic in experience.

The Hegemony of the Master

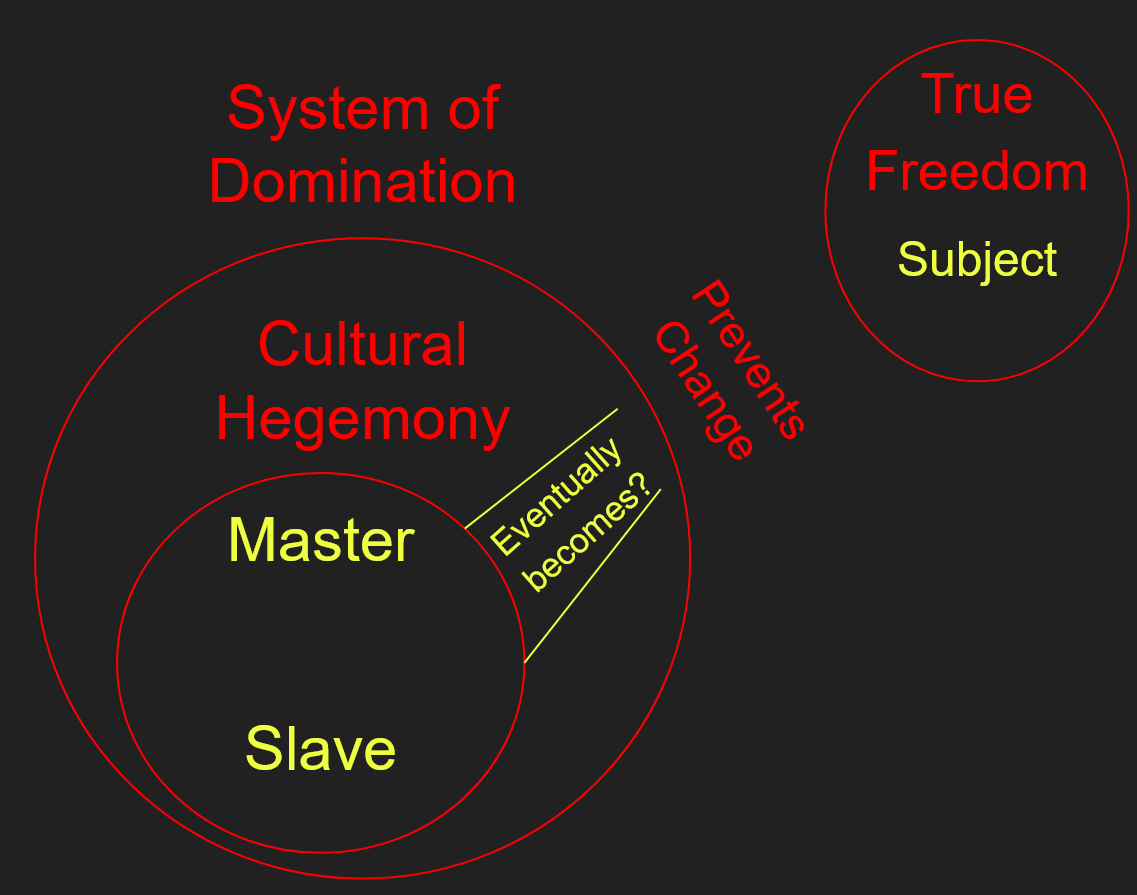

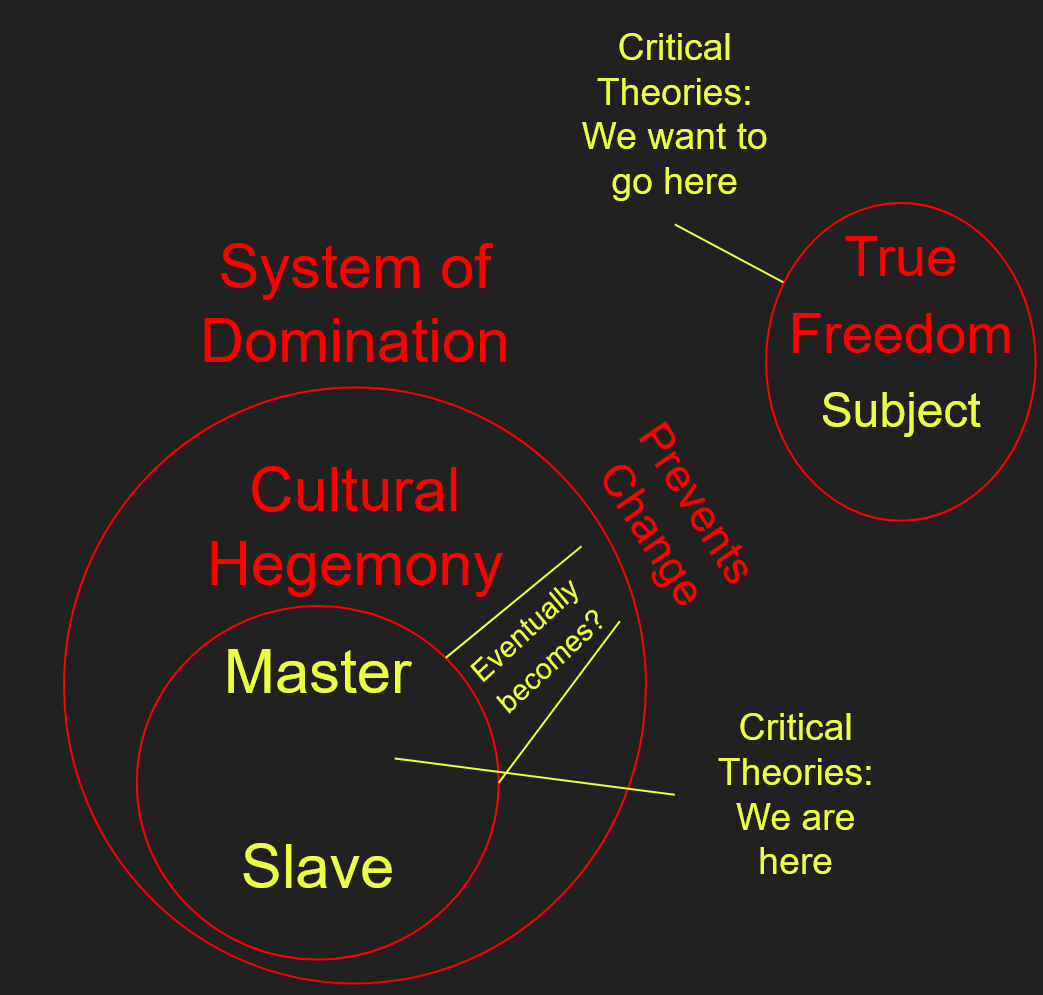

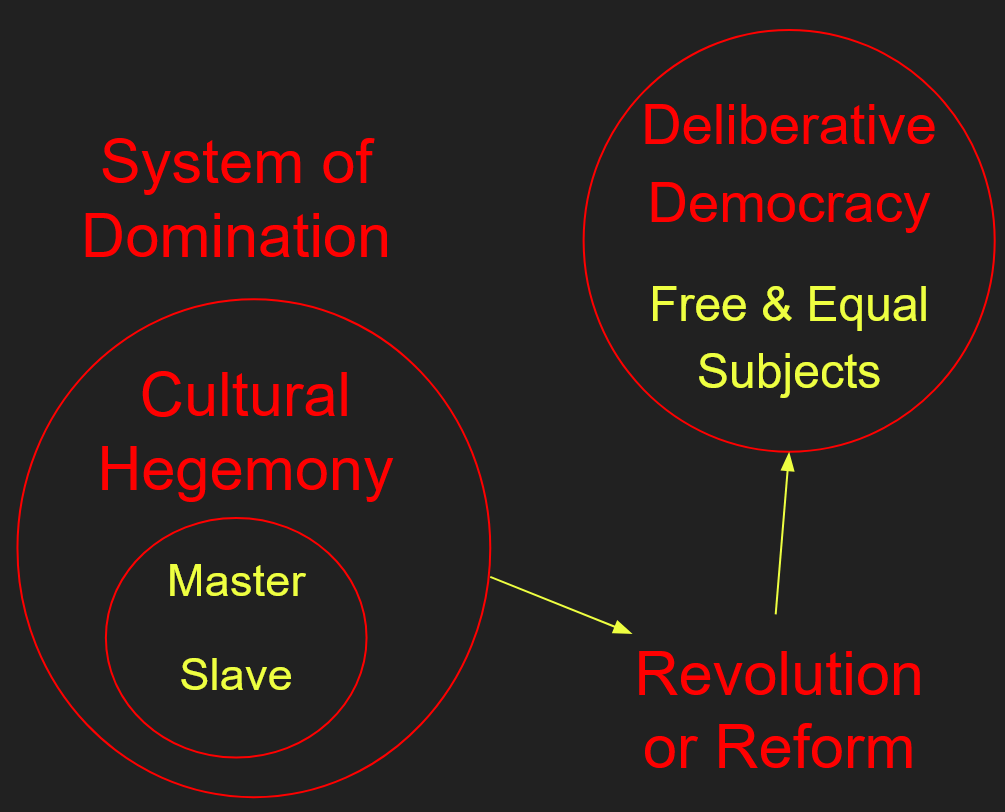

By Derrida’s time, it had also become common among left-wing philosophers to grant tremendous significance to language, as the medium through which the master-slave relationships in society are maintained. This hegemony, which was called the superstructure by Marx, and is seen as various kinds of systems of power by later thinkers, is heavily implicit in the master-slave-dialectic, as the world built by and for the master, until the two sides finally become one subject.

As marxist predictions failed, the role of the hegemony in legitimizing the Master’s rule received increasing attention from the theorists who wished to bring the dialectic forwards towards a more just world. A consequence is that hegemony as such became an object of study, derived from the dialectic, giving rise to impassioned and certainly not impartial analyses of how various hegemonies perpetuated themselves, ostensibly elaborating on the master-slave dialectic we have seen thus far. In this way, a facet of the dialectical model became the basis for marxist and post-marxist models of how societies operate, and is largely taken for granted today.

A particularly noteworthy facet of this facet is the idea that Hegemony instills false consciousness in the people living under it. Some place the false consciousness in the Slave, who sees his own submission as natural, inevitable, or the best way things could be. Others place it in the Master, who fails to recognize the injustice in his domination of the Slave. You may want to note that these are perfectly compatible, even if more specific words for which subject a given example concerns would make it more understandable. Such words were eventually produced in various theories. False consciousness in the Master is often called [something] privilege. In the Slave it is often called internalized [something].

If the dialectic is accepted as something we cannot help but to assume, its constituent parts and byproducts follow. Therefore, the practice of connecting experiences to Hegemony also constitutes production of objective knowledge in this view. This practice constitutes one particularly controversial version of the broader practice of problematization. Particularly controversial because not everyone accepts both the Kantian conception of objective knowledge and that the Dialectic is another foundation of how the world makes sense to us. Nonetheless, this form of problematization is common in modern feminist scholarship, to name one example.

The Counter-Hegemony

For left-wing philosophy, the existence of Hegemony requires the creation of a Counter-Hegemony - its dialectical opposite. Its purpose would be to instill a true consciousness in Master, Slave or both, what many critics of left-wing philosophy now call making them “woke”. In academic contexts, this is a critical, in several meanings of the word, including necessary, consciousness. Its purpose is to make Slaves recognize their oppression and Masters recognize what they are perpetuating, so they both work for the destruction of the system of domination, so that the dialectic can continue, or as some put it, we can get a revolution.

In the marxist tradition, which was early in its recognition that its Slave subject, the workers, were not automatically on board with continuing the dialectic, a theory of Hegemony was in the works already at the start of the 20th century. The solution of a Counter-Hegemony was described by the italian Antonio Gramsci, and is his claim to fame. With an analysis of what we might call the pillars upholding the Hegemony - family, education and law among them, it made sense to target these pillars for the creation of the Counter-Hegemony. This project was called a war of position because it sought to take the positions that create hegemony and repurpose them. It was later termed the “long march through the institutions” by a communist activist. Some might want to call it a conspiracy. Depending on who you ask, it is still on-going.

Critical Theories: Left-Wing Philosophy

The Critical Theorists of the Frankfurt School, who followed Marx and Hegel about 100 years later, first described critical theory as a kind of theory that, unlike traditional theory, did not just seek to understand the world, but also to change it. With the context of Hegel in particular, that is to say that critical theorists are conscious of their place in the dialectic, and develop theory through application, in the dialectical relationship between themselves and the world they try to change. The shortest formulation of this is that Critical Theory contains both Theory and Praxis, as discussed in part 1.

A consequence of note is that it is not obvious what of the things a critical theorist does is about communicating understanding, and what is about transforming social reality. I recently found a paper which described it as follows, paraphrased: “Critical Theory advocates for a dialectical notion of truth. According to this conception, apparent facts may be mere outdated and repressive aspects of social reality which should be eliminated rather than recorded. Therefore, critical theory does not aim for faithful description and generalization of data, but to be a part of, or guide for, praxis that will serve to eliminate the repressive aspects of social reality. The truth test is not observational verification, but evidence of the power to inspire successful practice.” It is worth noting that this sense of truth is far removed from common usage, and may confuse readers about which standard is being used whenever a critical theorist is involved.

While the Frankfurt School coined the term Critical Theory, it applies to all science and philosophy that meets these requirements, retroactively or in the future. Since the “critical” part of the name is a play on words and intellectuals love being clever like that, many fields who do Critical Theory will put it in their names. However, since being “critical” is generally regarded as a good thing, it is worth remembering that Critical Theory does not have a monopoly on the term; It mainly distinguishes itself in this regard by using “critical” with a layered meaning. The fields are critical of something, and they see themselves as critical to changing it in a desirable manner, often with reference to the dialectic. Essentially, this is left-wing philosophy.

Reflexive Truth & Social Constructs

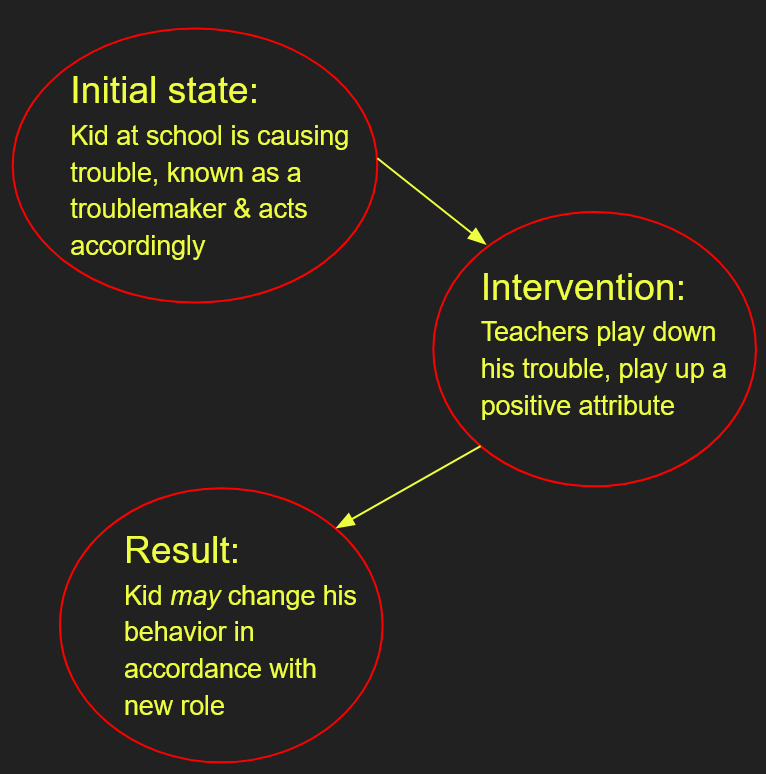

If the dialectical notion of truth strikes you as foreign, here is an example that might give you an idea of how it works. Imagine you have a school where one kid is acting out and causing trouble. Very likely, this kid is going to get a reputation for it. Knowing his reputation, he can easily act on it, trying to fit the role assigned to him by his previous actions and their consequences. This social assignment is what is called a Social Construct, something people have made true together, and here it means more trouble. However, teachers and others can recognize an ability to change in the kid, and speak to what the kid is good at otherthan making trouble, to avoid reinforcing the pattern, and perhaps even eliminate the pattern of behavior the kid was so often described by. This is successful practice by choosing not to speak to something that may be true at the time of speaking, but that might change if we just socially construct something else in its stead. The extent to which this works is debatable and results may vary, and employing this standard in science is certainly controversial, since it entails potentially wrong speculations on what and how things can change, but hopefully you now see how it can appeal to someone. Another term for this is reflexive truth, meaning statements which become true as a result of being believed. Critical theory-based scientists might decide to dismiss undesirable facts as social constructs, avoid recording them, and emphasize or play up other facts in order to facilitate desired social changes, hoping that in doing so, what they say will become the truth.

Denouncing the Dialectic of History

The first generation of Frankfurt School scholars is notable for two things in particular. First, as philosophers looking back at the dialectic of historicism, of consciousness becoming God through Reason. They noted the scale of one and then two world wars, as well as the creeping spread of rational argumentation in the sciences, and thought they saw the God that was being made real. It did not seem to be one that upheld the Kantian ethic, another formulation of which emphasized that one should always treat people as ends in themselves, and never only as a means to an end. The sciences and the logic of production in a capitalist system seemed to have gone into a union that required people to treat others as means to an end. To this point, Theodor Adorno, one of the major figures of this generation, once asked if a good life was even possible under capitalism. One of my sources goes as far as to indicate that Adorno thought that the dialectic as such led to misery, but that all the same, we had no choice but to participate in it, since it is all-encompassing. This amounts to a denunciation of the Dialectical God of historicism.

Another example, which did not go quite as far as Adorno: The first big name of the Frankfurt School, Max Horkheimer, also argued that sciences aspiring to neutrality let themselves be co-opted by nazis, as the nazis allowed for inhumane research and used the knowledge they gleaned from it to do horrible things. In order to avoid this anything-goes free science being useful to groups like the nazis, Horkheimer wanted science to embrace ethics, and attempt to create knowledge which would not be helpful to the nazi cause. What exactly that entails I can only speculate about, but it can easily be read as a call for science to be beholden to, or perhaps we should say co-opted by, Critical Theory, and for it to not report findings accurately if those findings are thought to help bad agents. With such a reading in mind, it is obligatory to ask who defines what constitutes a bad agent, and the extent to which science should be constrained by such concerns. No doubt there is a range of different answers here, from the reasonable to the totalitarian, with people all along the spectrum. In any case: Horkheimer demonstrates a clear mistrust of free science.

Aside about Aesthetics

Horkheimer’s mentality about science is not unique to him or necessarily limited to science. His contemporary, Walter Benjamin, devoted much time to creating a similar theory of aesthetics, that is, the philosophy of art. Benjamin worked with expressed intent to create a theory of aesthetics which would not serve fascists. Presumably Benjamin noted how fascists like the nazis had used art and ritual to appeal to the masses, and wanted to find a way to make this impossible, just as Horkheimer wanted to make science useless to the nazis. Since my sources are fairly vague on this point, as far as I am aware, this project went nowhere. Still, considering how the nazis embraced things like beauty, one form such a project might have taken is in trying to change either what people find beautiful or what artists create. As a composer myself I find it unlikely to have accomplished its goal in this form, and likely to produce exactly what it seeks to prevent, but remember, this is speculation.

The Way of the Negative

The second notable thing about the early Frankfurt School was the modifications they made to Marx’s version of the dialectic. Horkheimer puts it fairly simply, but I will simplify further. Marx failed to see that capitalism helps workers build a better life. He failed to see that freedom and justice are dialectical concepts, meaning that more justice meant less freedom, at least until synthesis, and he went wrong in forwarding an ideal society of free human beings.

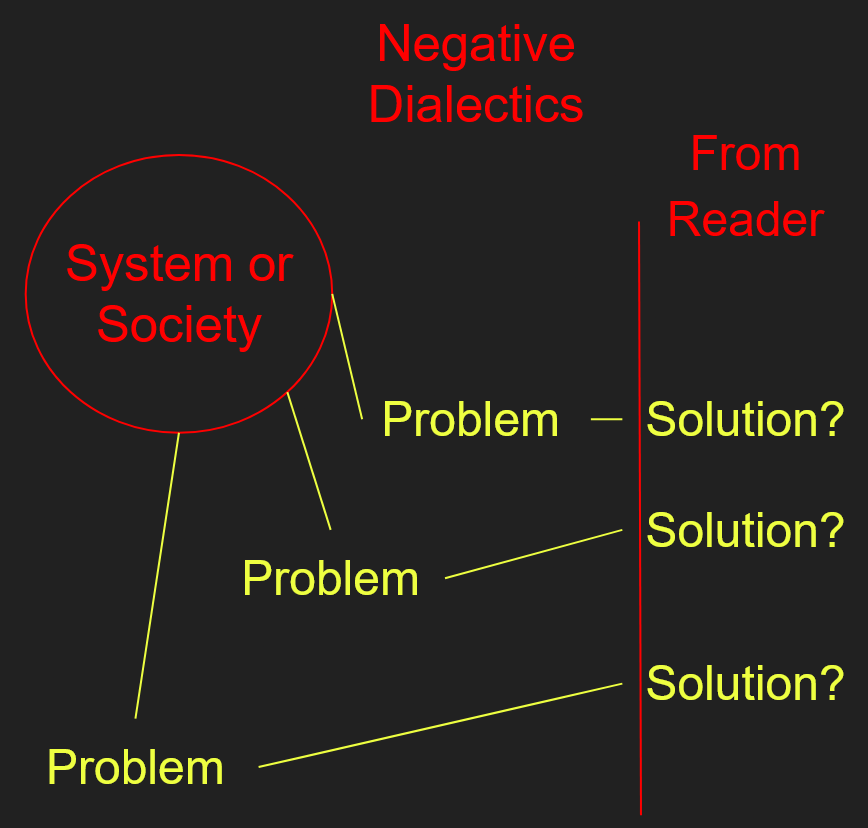

Critical Theorists eventually learned of the totalitarianism of attempted socialist regimes, that is, the step Marx predicted on the road to communism, led by a dictatorship of the proletariat, the Slave subject. It is not that they no longer wanted communism, but that they learned to be careful in advocating for anything. They would instead point to problems that needed changing, and leave the question of how it should be changed basically open, in order to avoid totalitarianism. This iteration of the dialectic took as its starting point a dissatisfactory situation, articulated a problem, and left the concrete - Hegel’s term - solution as an open question. It was dialectics, or philosophy as such, done negatively, and it had moved that much closer to the alchemical process of refinement, where impurities are removed to uncover the “gold” in the subject matter. Marcuse, a major figure from the Frankfurt School of the 60s, described it as a method which used the negative to make something positive. Adorno called this method “Negative Dialectics”, but you may also hear of the “Way of the Negative”.

Habermas Rationalizes the Negative

Habermas was a leading figure in the second generation of the Frankfurt school. He saw the rejection of Reason of the previous generation as going too far, because there are different rationalities at play. He noted scientific-instrumentalist rationality as the one his predecessors decried. He also noted a pragmatic rationality people use in day-to-day life, and a rationality of communication. The latter was central to his theory.

Habermas is seen by many as a moderating force on Critical Theory, taking away the sting of its criticism of contemporary society, a sting that was there in the previous generation and which would return with the next director of the Frankfurt School, Axel Honneth. This is because of Habermas’ less polemic stance on Reason, and the fact that he ran afoul of the Way of the Negative as a result.

First of all, Habermas regarded all his rationalities as having their place. When he echoed his predecessors about the rationality of science, he maintained that science was a powerful force which was reliant on this rationality, but that we should steadfastly prevent it from moving out into the social world, as that was the realm of the other two rationalities in their respective ways. In other words, he made a prescription.

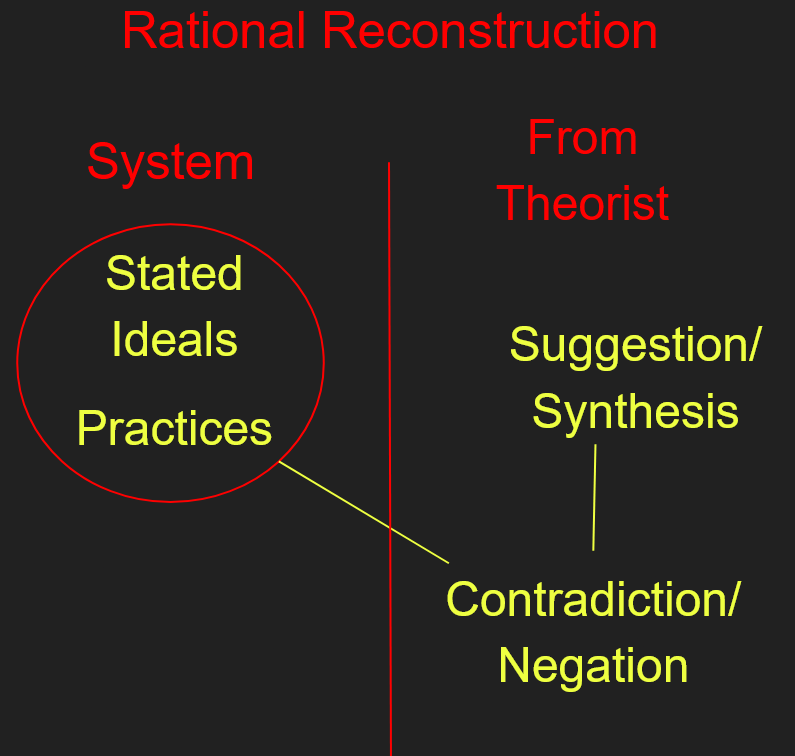

By retaining rationality, Habermas introduced a method to Critical Theory, which he called rational reconstruction. This method starts by observing how things are done and professed ideals, or attempting to articulate the ideals if they were implicit. Then it compares them, to see if there are any inconsistencies, or contradictions, between Theory and Praxis. This method is meant to aid people in living up to their own ideals, thereby avoiding totalitarianism by seeking the standard for evaluation from the target of evaluation, rather than from the critical theorist himself. The method can be applied to anything with ideals and practices, including and perhaps especially Critical Theory itself.

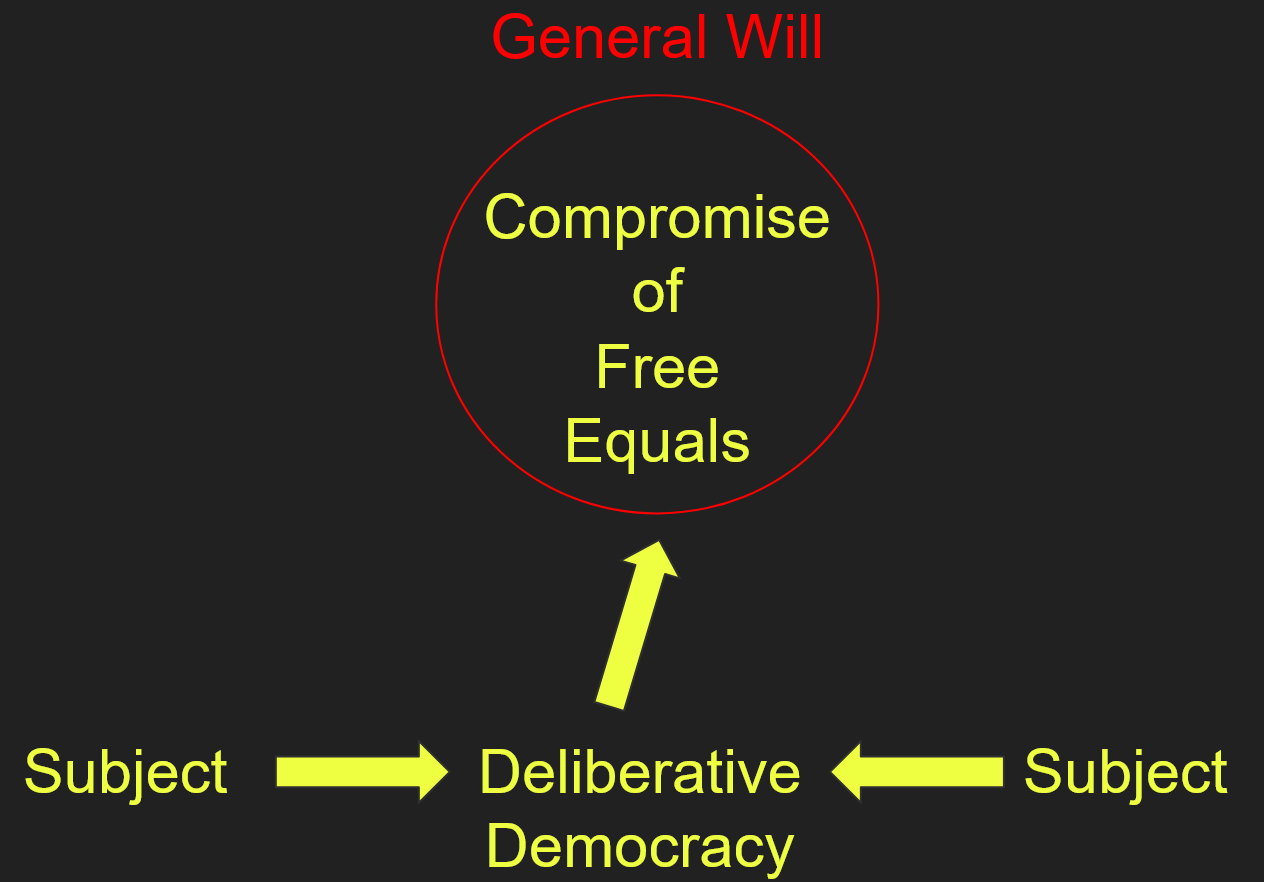

Deliberative Democracy

With Habermas, the rationality of communication basically took the place of Hegel’s Consciousness with Reason in the dialectic of History, by way of what he called deliberative democracy. Deliberative democracy entails a meeting of all parties who are affected by or concerned about an issue, where they all recognize each other as equals and participate of their own volition, a free meeting of equals. They would discuss the problem and how best to solve it until a consensus is reached. This does not mean that they would all be satisfied by the agreement, but that they would all agree that their conclusion is the solution that best serves all the involved interests at once. By freely deliberating like this, Habermas thought that the different parties involved would all feel an obligation to follow through on their agreement over their own interests, thereby producing a general will and allowing them to act as one subject.

With this ideal, Habermas fell out with many of the other Critical Theorists, who saw it as getting dangerously close to the totalitarian side of Hegel, and who also disliked how much his ideal resembled the state of contemporary society.

Deliberative Democracy: After the Dialectic?

I would like to call attention to the requirements that participants are free and equal. It is indeed the case that many would consider modern societies as consisting of participants who are free and equal insofar as this is possible. Critical Theorists are an exception to this. It is not at all clear that Habermas regarded his model as reflecting contemporary society, though it is clearly implementable at a small scale. If freedom means freedom from “heteronomous interests” to use Marcuse’s phrase, from being influenced by others, then you are not free when parents want you to do things for them, when you need money to get things you want, or when you are beholden to a partner. If equality means “no power-difference” like there would be between Master and Slave, which prevents true friendship, would not deliberative democracy require the abolition of all Master-Slave relationships? There is at least a case for this reading. With this reading, deliberative democracy is a different thing to critical theorists than it is for people who do not accept these premises. To Critical Theory, deliberative democracy may be better understood as a description of how things would work at the end of the dialectic.

It is fairly common for Left-Wing philosophers to regard democracy under capitalism, or any other name for the current Hegemony, as false, incomplete, or something else to this effect. If we follow the theories of false consciousness, people voting for what they “want” under an unjust system will be voting what the system wants them to want, and not what they truly want, which Critical Theories might know and understand better than the voting populace. If you ever wondered about the logic of self-styled “democratic” but seemingly totalitarian countries, they can be democratic in the sense that the theorists understand what the people want better than the people themselves do, and therefore don’t need to listen. Even when this is false, it is a good strategy for their hegemony, which will persist until the dialectic finally ends, which, to Marxists, means when there are no more states at all, and everyone is free and equal. Since these states are still states among other states, that time has not come, but at least these societies proclaim they are ready or at least preparing for it.

Social Misrecognition

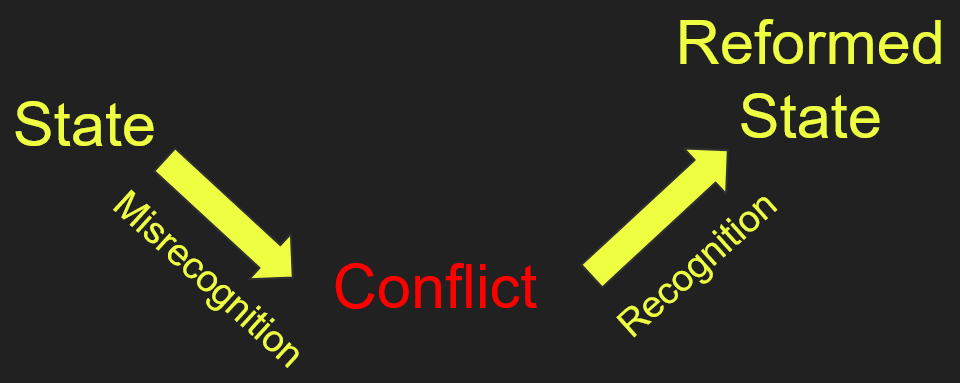

In one of the most recent turns dialectical philosophy has taken we have the theory of Social Misrecognition, which was Honneth’s attempt at reconciling the Critical Theory of the Frankfurt School with Postmodern Theory. He was far from the only one who was interested in combining a Critical Theory with Postmodern Theory in the 80s, and we will need to understand a bit more about Postmodern Theory soon, but for now we can keep it simple, as it requires some understanding of Postmodern Theory to even see how it plays into Honneth’s model.

Honneth took Habermas’ deliberative democracy as the starting point for his theory. He quickly honed in on and emphasized the aspect that all parties to the deliberative process would have to be recognized as equals. In classical dialectical fashion, he turned this on its head, and noted that if any party in the deliberation experienced misrecognition, not being seen as an equal, that would cause conflict.

This might seem banal, but it pointed out a new edge for Critical Theory. With this development, any experience of misrecognition, and you will recall that the issue in the master-slave-dialectic is that the parties are not recognizing each other as equals, can be connected to the dialectic as objective knowledge, and provide an imperative for social change, for Praxis.

Generalized Misrecognition

With this theory of Misrecognition, you might think that the experience in question is an individual experience. This is not necessarily the case. Anywhere a master-slave relationship can be found, theory will expect an experience of misrecognition in slave-subjects. This experience would characterize a critical consciousness in Slave-subjects, which Critical Theorists generally want to awaken so the dialectic can proceed. It is also fairly easy to contextualize struggles such as for civil rights as struggles for recognition, which, again, connects the relevant experiences to the dialectic, either directly or via some section of it. For example, the Hegemony and how it instills a false consciousness in people will make some Slave-subjects think their situation is acceptable.

If the dialectic is all about recognition, as Honneth emphasizes, we might ask what constitutes proper recognition. Honneth had his answer in three layers: Love, contrasted with threats to bodily integrity, Right, contrasted with threats to social integrity such as exclusion, and Solidarity, contrasted with threats to inherent worth and honor, which he wanted institutions to protect and facilitate. The topic has led to some debate between different strands of Critical Theory, notably in the form of a book Honneth co-authored with a feminist, about recognition and redistribution. What is certain is that people are unlikely to agree about this question, even when we try to keep it simple by only looking at one dimension of oppression, an issue which is further muddied by the problem of false consciousness in a manner that can be illustrated by a simple question: How do we determine if people who are satisfied are satisfied because of false consciousness? In my years of study I have not found a satisfying answer to this question. If someone knows one, I would appreciate it if I could be pointed towards it. Until then, it seems like the only answer is “we don’t”. Presumably it constitutes a contradiction that has to be worked out through Praxis.

Against Self-criticism

Following all of these theorists, a Danish theorist named Willig forwarded a new program for Critical Theory. To keep it brief, Willig contended that self-criticism made people judge themselves, and sometimes too harshly. Moreover, these criticisms stopped people from criticizing the greater social system. Willig’s new program is simple: Critical Theory is to seek any and all criticisms of the system and bring them to social movements and political parties. The method was to be “negative” and “phenomenological”, that is, experience-based, which should include experiences of misrecognition. Doing self-criticism rather than system-criticism would limit the potential for systemic change, and help people with self-realization, a word which comes from the action of making yourself into a thing, an object, which is to say, not a subject, and not a source of change.

Revolution or Reform: Does History End?

Critical Theorists started by drawing on Marx and Hegel, both of whom envisioned an end of history with religious undertones. With their development of negative dialectics, and Honneth’s speculative analysis of Habermas’ speculative ideal, they have moved into a model where an end to the dialectic is no more than something to hope for, as experiences of misrecognition and ensuing complaints might still arise in deliberative democracy. Thus, many Critical Theorists have abandoned attempts at articulating what the end-goal looks like, to instead focus on the process. Some aspects of Theory indicate a need for revolution to end Hegemony, so the false consciousness it produces can be taken out at the root. Others encourage reform, and try to make the perfect society out of the current society. Later theorists like Habermas and Honneth can appeal to both camps, that is, the entirety of left-wing philosophy.

What of Internal Praxis?

A curiosity is that the process, which started out with reference to alchemy, is completely externalized with negative dialectics, most clearly with Willig. Alchemists, on the other hand, initially thought the process had to be applied to the alchemist himself as well. To the tradition following Hegel, we might call it a Praxis of the Spirit. This was actually forwarded in another strain of Marxist Theory: Critical Pedagogy. Here, Freire saw a need for a perpetual Praxis to change the world while also reflecting on one’s own activity; A marriage of Theory and Praxis, where the work this does on one’s own soul is important, too. Freire thought we would need a perpetual revolution for this, to continually refine ourselves to make a better world. Right now I made it sound like this marriage of Theory and Praxis is new with Freire, but it is my impression that in left-wing philosophy, it isn’t really considered Praxis at all if it isn’t wedded to Theory, specifically to a Critical Theory. From the start, the prescriptive meaning of Praxis was wedded to Theory, and involved reflecting on one’s activities. In other words, what Freire offered was first and foremost a restatement of the traditional view within left-wing philosophy, of Praxis as something that resolves internal contradictions through reflection while trying to change social life.

I will not delve deep into the pedagogical side of dialectical philosophy here. This is long enough as it is, and as you can see, it doesn’t really add that much. It is enough to note the following. It regards teachers as the Master subject on behalf of Hegemony, and the Praxis it forwards is a Praxis of the critically conscious Master. The critically conscious Master has to be open, reflective and careful in order to accommodate the criticisms from the Slave. Also, that this is necessary, or critical, for the dialectic to be brought forward so the perpetuation of the domination in Master-Slave relationships can be brought to an end.

Unlike critical pedagogy, Postmodernism and Marcuse’s contributions to left-wing philosophy warrant some more attention for what they added to the dialectical logic of left-wing philosophy. A final major topic is intersectionality, which grew out of the two of them..

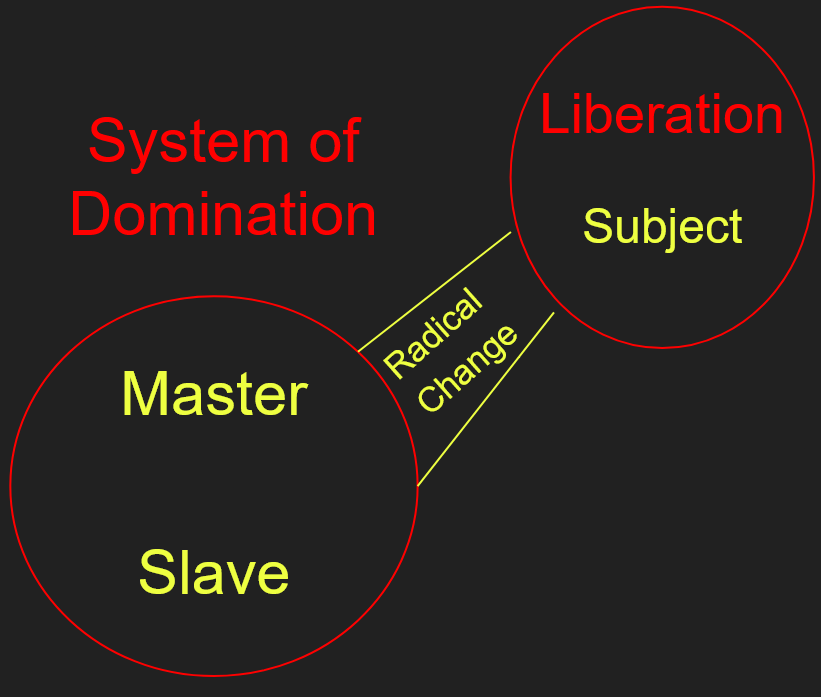

Communism is really Liberationism

With Marcuse, many ideas that were already in Critical Theory found great popularity in the 60s. Recall that this is before Habermas redeemed some kinds of rationality in some domains to some Critical Theorists. This is important, because Marcuse’s ideas would gain tremendous influence in many left-wing milieus without Habermas’ moderating force. First of all, Marcuse forwarded a new name for the end goal, noting that their desire was for liberation, and for socialism without bureaucracy.

This was not least an attempt at distinguishing their desire from what had been done in the Soviet Union. It was also the result of incorporating Freud’s psychoanalysis in the theory, concluding that the Hegemonic Capitalist system channeled people’s eros into productive labor. This is very simplified, but the idea is that erotic drives needed to be liberated, and that this could not happen under Capitalism.

The emphasis on liberation, or emancipation, was in the theory from the start. In the master-slave dialectic, one dominates the other, thereby limiting his freedom. But the dominator also finds himself dependent on the Slave. Surely freedom is independence? Moreover, even in Hegel the end of the dialectic constituted liberation in the sense that it would see all subjects become one in God, whose omnipotence implies freedom. In Marx, Communism is about freedom from the bondage of Capitalism, and Critical Theorists always emphasized their purpose as challenging “repressive” or “oppressive” systems in order to aid in the emancipation of free subjects. And it does not regard anyone as free before everyone is free at once, instead merely seeing people as enjoying prisons with varying degrees of comfort. Thus, Marcuse’s emphasis on liberation was largely a rebranding of the ideas in the tradition, done not least to seek common cause with various contemporary liberation-movements. This rebranding had enough power to support and connect people in these movements who shared a worldview built on Marx and Hegel. These portions of these movements, we may call Liberationists, in Marcuse’s spirit. They are characterized by a project that goes much further than their one-dimensional, usually liberal allies.

One-Dimensional Minds

Marcuse also echoed his predecessors with the notion that rationality was part of the Hegemony, part of what perpetuated the false consciousness that maintained the oppressive system. This idea was later pinpointed by a liberationist who followed in his tracks, Audre Lorde. She argued that rationality was a tool of the Master, and that these tools would “never dismantle the Master’s house”, though they might temporarily beat him at his own game.

Why is rationality viewed in this way? Because many of the arguments against liberationists appealed to rationality. They might call a proposed solution practically impossible. Maybe it runs counter to an important principle, or maybe rationality will be invoked to say that this, whatever this is, is as good as it gets. In these ways, rationality stands in the way of liberation. It protects the state of things, the status quo, by setting the dimensional limits of thought for people operating within the hegemony of the Master. This is without even considering its role in aiding Capitalism in discouraging people from treating others as ends-in-themselves, which adds another line of moral attack on rationality.

To get out of the one-dimensional system of rationality and its loyalty to the Master, Marcuse forwarded the idea that we should rely on imagination, since it breaks the boundaries of rationality. Can we imagine that things could be different? Then we can decry the way things are done today, and search for ways to make our dreams reality. This practice can generally be called “reimagining”. It reflects how Marcuse thought that negative dialectics could give rise to something positive, as the imagination is spurred by something negative to imagine something better. The most pop-cultural reflection of this is John Lennon’s “Imagine”, which was supposed to be the Communist Manifesto in the form of a song.

As has become a pattern here, this idea was also latent in some of Marx’s works, though easily overlooked. Marx regarded it as a specifically human trait to be able to imagine something and then to create it, and that in this, Man can recognize himself as Creator. In this form the idea is actually fairly common and not at all limited to Marx, but when combined with the dialectical idea that Man creates Society which in turn creates Man and vice versa, it becomes a matter of what was later called social constructs, things humans have made together, what can be made and what can not. It should therefore not be surprising if later iterations increasingly focus on getting everyone on the same page, heavily implying that in doing this, Man can achieve omnipotence and bring into being anything, including Heaven. Marcuse seems to have been aware of and largely thought along these lines.

Two Kinds of Humanism

This is a tradition of humanist thought which puts humanity as such and in its entirety in the place God formerly held, which stands apart from the tradition of humanist thought which simply holds that every human has immeasurable and unique value. I call the former Collective Humanism and the latter Individual Humanism. I think the former, with its desire to get everyone to agree in order to make the perfect world, contains the ideas of Hegel’s historicism, and still seeks to bring the dialectic to its conclusion in this way, thereby creating a singular subject, which will be God.

Creating A New Sensibility

Marcuse thought that in order for socialism to become reality, it would require what he called a biological foundation. He saw this in trying to instill an attitude of absolute intolerance of domination in all its forms in people, so they could come together in solidarity as one movement to fix all Master-Slave relationships. He called this attitude a new sensibility. Sensibility is a term in philosophy which was present in Kant, which generally means something you decide a priori, something you just decide ahead of or regardless of experience. For example, when I mentioned Levinas earlier, his ethic of responsibility in the encounter with the Other also described it as a sensibility. Marcuse was particularly interested in instilling it in students, as they had a life-time of Praxis ahead of them from within the Hegemony. Some of his students suggest that he succeeded with them.

Creating a new sensibility makes a lot of sense in the context of the dialectic. At least since Marx, there has been an emphasis on how Man creates Society which then creates Man, in a dialectical relationship of the kind we saw with the hermeneutic circle. By consciously trying to create a society which then creates a specific new sensibility in Man, one should therefore be able to guide the development of this dialectic. As should be clear with this, it is really just a practical application of the concept of hegemony, and a restatement of Gramsci’s idea of a counter-hegemony.

The Working Class Lost Revolutionary Energy

A final key point with Marcuse, setting aside his famous and freely available discussion on the need for liberating tolerance to be repressive tolerance, with no tolerance of the right but tolerance for all impulses of the left, is his observation, echoing Horkheimer’s conclusion, that Capitalism is making the lives of Workers better. With better lives, the workers are not getting more miserable. This means that they are no longer a subject of the dialectic, or that they have been successfully turned into an object, a tool, of the Master. To progress, then, the dialectic must find other Slave subjects to move through.

Marcuse saw potential for this in the various liberation and civil-rights movements around the world at his time, and essentially argued that Critical Theory should redirect its attention to groups like women, black people, and what they later turned into an acronym for all those who in some way differ from the norm in anything having to do with sex or gender. These groups demonstrated revolutionary energy, and showed a lot more promise for the dialectic. We may summarize it as a form of Marxism that has shifted away from the master-slave relationship it initially concerned, but which retains a lot of the ideas of Marx, as well as the entirety of Hegel’s dialectical logic, only applying it to identity categories it deems more potent. We will get back to it in part 3 with Intersectionality after a brief explanation of postmodernism.

This is part of a three part series.

Read part one here:

Trygve Taranger is an autodidact software developer, data scientist and musical composer with a Master’s degree in Media Practices. While in university, he accidentally found himself learning about Critical Theory every single year in most of his courses. Trygve is most active on X as @CuriousnTT, where he explores different ways to think about things.